Reviewed by Lexie CornerMay 28 2025

When it comes to health, women age differently than men, particularly with regard to conditions such as cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disorders like dementia and Parkinson’s. Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now proposed a new explanation.

In aging female mice, genes on the second X chromosome, normally inactive, become reactivated. This genetic shift may play a role in how women’s health changes later in life.

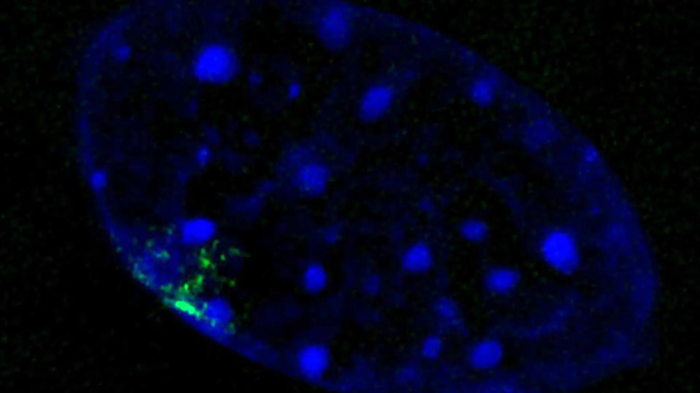

In female mammals, one of the two X chromosomes is usually inactive and forms the so-called Barr body. The image shows a cell nucleus with the Barr body marked in green. Image Credit: Daniel Andergassen / Technical University of Munich

In female mammals, one of the two X chromosomes is usually inactive and forms the so-called Barr body. The image shows a cell nucleus with the Barr body marked in green. Image Credit: Daniel Andergassen / Technical University of Munich

Unlike men, who have one X and one Y chromosome, women carry two X chromosomes in each cell. To balance gene activity between the sexes, one of the X chromosomes in females is largely inactivated. It folds into a dense structure known as a Barr body, making most of its genetic information unreadable. Without this inactivation, genes on the X chromosome would be expressed at double the level in women compared to men.

Scientists have long known that some genes can escape this inactivation, resulting in higher gene activity in women. These escapee genes are believed to play a role in the development of certain diseases.

We have now shown for the first time that with increasing age, more and more genes escape the inactivation of the Barr body.

Dr. Daniel Andergassen, Group Leader, Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Technical University of Munich

The journal Nature Aging published the study.

Inactive X chromosome Loosens with Age

The researchers examined major organs in mice at different ages. In older mice, the proportion of X-linked genes that escaped inactivation doubled compared to adult mice, rising from about 3 % to 6 %. In some organs, the percentage was even higher; for instance, around 9 % of X-linked genes were active in the kidneys.

With aging, epigenetic processes gradually loosen the tightly packed structure of the inactive X chromosome. This primarily occurs at the ends of the chromosome, allowing genes in those regions to be expressed again.

Sarah Hoelzl, Study First Author, Technical University of Munich

Many Reactivated Genes are Linked to Disease

Many of the genes that become reactivated with age are associated with disease.

“Our findings are based on mice, but since the X chromosome is very similar in humans, I believe the same may happen in aging women,” remarked Daniel Andergassen.

If this holds true in humans, future studies will need to examine how reactivation of these genes affects disease development. According to the team, increased gene activity with age could have both beneficial and harmful effects. For example, ACE2 - one of the reactivated genes in the lungs - may help protect against pulmonary fibrosis. On the other hand, higher TLR8 activity could contribute to autoimmune conditions like late-onset lupus.

A New Perspective on Sex-Based Differences in Disease

Andergassen added, “Sex differences in age-related disease are incredibly complex. So far, scientific explanations have mostly focused on hormonal or lifestyle factors. While the role of the X chromosome and certain escape genes has been previously studied, the finding that many genes on the inactive X can reactivate with age opens up entirely new avenues of research.”

Andergassen said, “This insight could provide an alternative to hormonal explanations and enhance our understanding of sex differences in age-related diseases, potentially even addressing the fundamental question of why women statistically live longer.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Hoelzl, S., et al. (2025) Aging promotes reactivation of the Barr body at distal chromosome regions. Nature Aging. doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00856-8.