Discover how mapping proteins in space transforms our understanding of cellular organization, disease progression, and translational biomedical research.

Image credit: Love Employee/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Love Employee/Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Spatial proteomics is an advanced extension of bulk and single-cell proteomics that preserves information on where proteins are located within cells and tissues. Traditional proteomics measures total protein levels but typically disrupts tissue architecture, causing loss of spatial context needed to understand biological function. However, cell behavior and disease progression critically depend on the subcellular and tissue-level localization of proteins, cell-to-cell interactions, and the surrounding microenvironment.1

This article discusses key technologies, recent advances, current challenges, and emerging biomedical applications of spatial proteomics.

Proteomics 101

Video credit: JAMANetwork/Youtube.com

Why spatial context transforms biological interpretation?

A protein's function is closely linked to its location, interaction with other molecules, and the surrounding tissue structure; mislocalization can disrupt normal cellular regulation and contribute directly to disease pathogenesis. Conventional bulk proteomics can report identical protein abundance across samples, yet these similarities may conceal profound functional differences arising from spatial organization and context-dependent relocalization events.1,2

Spatial proteomics overcomes this limitation by preserving positional information, allowing proteins to be studied in their native cellular and tissue context. This approach enables direct analysis of cell–cell interactions, identification of functional tissue niches, and detection of spatially restricted disease-associated alterations. Such capabilities are particularly critical for understanding complex disorders, including cancer, immune-mediated conditions, and neurodegenerative diseases, where cellular heterogeneity and microenvironmental interactions fundamentally shape disease progression and therapeutic response.2

Need to save this article for later? Download your free PDF copy here!

Spatial proteomics technologies

Spatial proteomics integrates imaging, mass spectrometry, and proximity-based strategies to preserve protein localization while enabling molecular analysis in intact tissues. Rather than relying on a single platform, researchers employ complementary technologies optimized for different spatial scales and biological questions. These approaches balance spatial resolution, proteomic depth, and throughput, collectively enabling comprehensive mapping of complex tissues.1

Imaging-based approaches

Imaging-based spatial proteomics relies on antibody- or probe-based labeling combined with fluorescence or ion-based imaging to visualize proteins directly within tissue sections. These methods preserve tissue architecture and allow high-resolution mapping of protein expression at cellular and subcellular levels.

Multiplex immunofluorescence and DNA-barcoded antibody strategies enable simultaneous detection of dozens of proteins, making them well-suited for studying tissue organization and microenvironments. However, imaging approaches remain constrained by antibody availability, cross-reactivity, and predefined target panels, limiting unbiased proteome-wide discovery.1

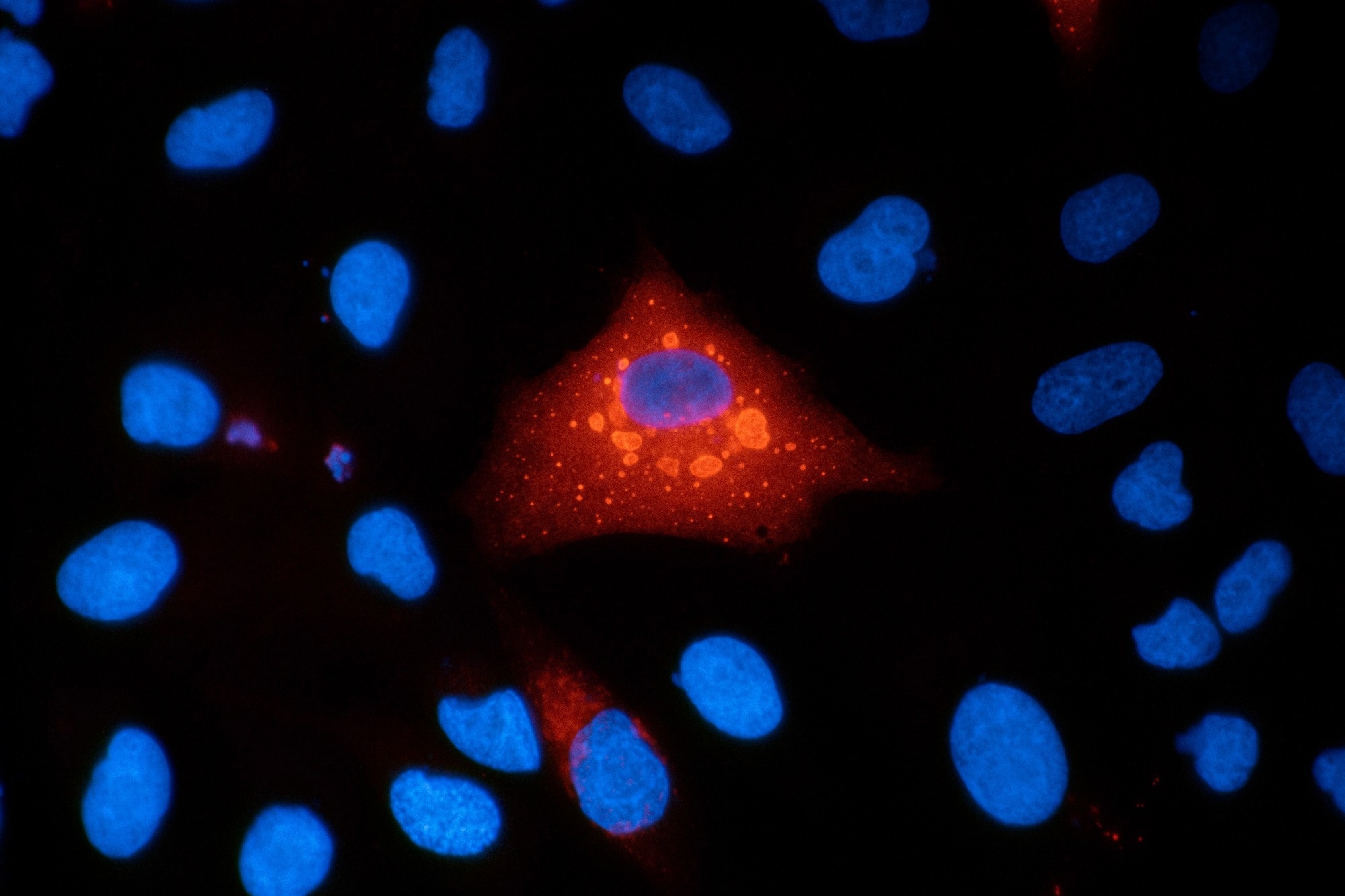

Immunofluorescence micrograph of A549 human lung carcinoma cells stained for p62 (SQSTM1) and DAPI, showing intracellular protein localization and cell nuclei. Image credit: VANOXmicroscopy/Shutterstock.com

Immunofluorescence micrograph of A549 human lung carcinoma cells stained for p62 (SQSTM1) and DAPI, showing intracellular protein localization and cell nuclei. Image credit: VANOXmicroscopy/Shutterstock.com

Mass spectrometry-based approaches

Mass spectrometry-based spatial proteomics enables broader and largely unbiased protein detection. Techniques such as mass spectrometry imaging and laser capture microdissection, coupled with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, provide deep proteome coverage and support discovery-driven analysis. These approaches can quantify thousands of proteins within defined tissue regions, facilitating biomarker discovery and pathway-level insights.

The primary trade-off lies between spatial resolution, sensitivity, and throughput, as higher resolution often requires longer acquisition times and more complex sample preparation.1

Proximity labeling and interaction-focused methods

Proximity labeling and interaction-focused strategies capture proteins within localized microenvironments or interaction networks, revealing functional protein associations that are difficult to detect by imaging or bulk analysis alone. These methods are particularly powerful for mapping protein–protein interactions and dynamic subcellular niches but are generally limited in tissue-scale applicability and spatial coverage, restricting their use in highly heterogeneous samples.1

Imaging approaches prioritize spatial resolution, mass spectrometry emphasizes proteome depth, and proximity labeling focuses on functional interactions; the optimal strategy depends on the biological question, sample type, and required spatial scale.1

Recent advances expanding spatial proteomics capabilities

Over the past three years, spatial proteomics has advanced rapidly, driven by improvements in mass spectrometry sensitivity, labeling chemistries, and computational analysis. Low-input and automated workflows now enable robust proteome-wide localization mapping from limited clinical material. Increased multiplexing and streamlined sample preparation have expanded applications from cell lines to complex tissues, including biopsies and formalin-fixed samples.3

In parallel, in situ methods for studying protein–protein interactions have matured. Advanced proximity labeling systems, including fast enzyme-based and light-activated approaches, enable capture of transient interactions with high temporal and spatial precision. These techniques reveal dynamic protein networks and microenvironments that cannot be inferred from abundance measurements alone.3

Recent developments have also improved the ability to resolve cellular and tissue heterogeneity. By integrating spatial proteomics with imaging and single-cell technologies, researchers can generate multidimensional protein maps that link localization, interaction, and function. Combined with advanced bioinformatics, these approaches represent a major advancement in spatially resolved proteome analysis.3

Data analysis, integration, and challenges

Spatial proteomics generates high-dimensional datasets that integrate imaging information with quantitative protein measurements, making data analysis inherently complex. Key challenges include balancing spatial resolution, proteome depth, and throughput, as optimizing one factor often compromises another. Additional obstacles include variability in sample preparation, lack of standardized analytical pipelines across platforms, and difficulties integrating spatial proteomics with co-localized omics layers such as transcriptomics.1

To address these challenges, specialized computational frameworks and machine learning approaches have been developed to align spatial coordinates, segment cell populations, and integrate multimodal datasets. These tools improve reproducibility and enable the extraction of biologically meaningful patterns from complex spatial data, supporting both basic research and translational applications. 1

Biological and translational applications

Spatial proteomics enables detailed mapping of tissue organization and functional cell states by linking protein localization to cellular context. In disease research, it facilitates systematic profiling of tumor and immune microenvironments, uncovering spatially defined signaling networks, metabolic programs, and cell–cell interactions that drive pathology. The approach has also provided critical insights into neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases, where aberrant protein localization plays a central pathogenic role.

Beyond mechanistic understanding, spatial proteomics supports biomarker discovery, drug target validation, and development of spatially informed diagnostics, although widespread clinical implementation remains challenged by standardization and scalability requirements.3

Conclusion

Spatial proteomics extends beyond measuring protein abundance by systematically mapping protein localization within cells and tissues. Current approaches enable analysis of protein positioning, interaction networks, and tissue architecture but continue to face challenges related to resolution, depth, throughput, and standardization.

Ongoing advances in mass spectrometry, imaging technologies, and computational analysis are steadily overcoming these limitations, positioning spatial proteomics as a powerful complementary tool for understanding cellular organization in health and disease.3

References and Further Reading

- Wu, M., Tao, H., Xu, T., Zheng, X., Wen, C., Wang, G., Peng, Y., & Dai, Y. (2024). Spatial proteomics: unveiling the multidimensional landscape of protein localization in human diseases. Proteome Sci. 22. DOI:10.1186/s12953-024-00231-2, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12953-024-00231-2

- Xu, Y., Lih, T. M., De Marzo, A. M., Li, Q. K., & Zhang, H. (2024). SPOT: spatial proteomics through on-site tissue-protein-labeling. Clin Proteom. 21. DOI:10.1186/s12014-024-09505-5, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12014-024-09505-5

- Bernardini, C., Däther, M., & Traube, F. R. (2026). Advances and Applications of Spatial Proteomics: From Organellar Maps to Clinical Translation. ChemBioChem. 27(1). DOI:10.1002/cbic.202500616, https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cbic.202500616

Last Updated: Jan 29, 2026