Researchers who were exploring ways to establish the feasibility of batches of small liver organoids have now identified a new testing approach that may have far wider implications.

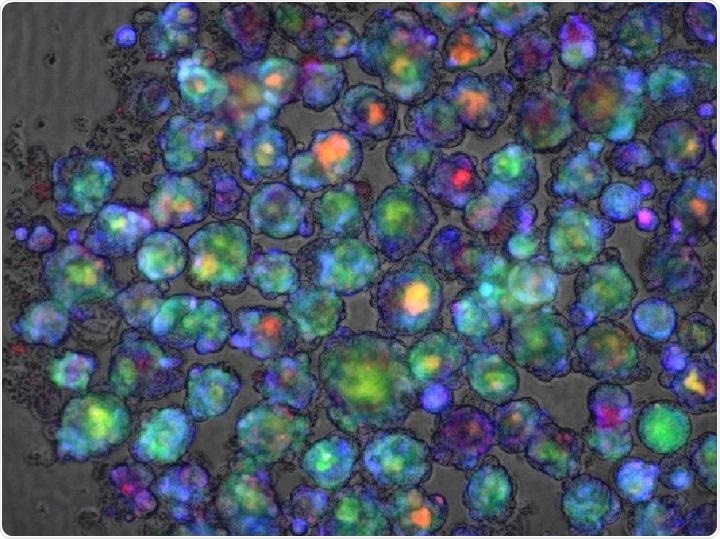

Color-enhanced confocal microscope image of a liver organoid used in a study in Nature Medicine that reports success at developing a polygenic risk score for predicting whether a medication will cause liver injury. Image Credit: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Published in the Nature Medicine journal on September 7th, 2020, the new study has reported about the identification of a “polygenic risk score” that demonstrates when a medication, be it an experimental drug or an approved one, poses a danger of drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

The study was performed by a group of researchers from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. in Japan, and many different research centers in Japan, Europe, and the United States.

The latest discoveries bring scientists one step closer to solving an issue that has long frustrated the drug developers.

So far we have had no reliable way of determining in advance whether a medication that usually works well in most people might cause liver injury among a few.”

Jorge Bezerra, MD, Director, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Jorge Bezerra continued, “That has caused a number of promising medications to fail during clinical trials, and in rare cases, also can cause serious injury from approved medications. If we could predict which individuals would be most at-risk, we could prescribe more medications with more confidence.”

Bezerra was not involved in the study.

Now, that dependable test may soon become a reality.

Our genetic score will potentially benefit people directly as a consumer diagnostic-like application, such as 23andMe and others. People could take the genetic test and know their risk of developing DILI.”

Takanori Takebe, MD, Study Corresponding Author and Organoid Expert, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Takebe has been exploring ways to grow liver “buds” for large-scale application in the study.

The researchers created the risk score by re-assessing scores of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that had detected an extended list of gene variants that might point to the possibility of a weak reaction in the liver to numerous compounds. The team combined the information, then applied many mathematical weighting techniques, and finally identified a formula that seems to work.

- The risk score considers over 20,000 gene variants.

- The researchers verified the prediction power of the risk score in organoid tissue, in cell culture, and by applying patient genomic information that is already on file.

- The risk score was valid in tests that involved over a dozen drugs, such as amoxicillin-clavulanate, bosentan, cyclosporine, carbamazepine, diclofenac, flutamide, troglitazone, ketoconazole, tolcapone, acetaminophen, tacrine, and methapyrilene.

- The test is suitable for different types of medications since the risk score targets a group of common mechanisms that are involved in the way a drug is metabolized by the liver, including oxidant stress routes in liver cells and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress—a disruption of the function of cells that occurs when proteins cannot fold correctly.

How can a risk score help?

This would allow clinicians to run a rapid genetic test to determine patients who are at a higher risk of sustaining liver injury before prescribing the drugs. The outcomes might prompt a physician to order more frequent follow-up tests to detect the early signs of liver damage, modify the dosage, or change the drugs completely.

In the field of drug research, the test can help physicians exclude individuals who have a high risk of sustaining liver injury from a clinical trial so that the advantages of a drug can be more precisely evaluated.

Over the years, liver toxicity resulted in several drug failures. Takebe stated that both the drug maker and patients were disappointed when a promising diabetes treatment, known as fasigliam, was withdrawn earlier in 2014 during phase three clinical trials. A few participants (at a rate equivalent to around 1 in 10,000) experienced increased enzyme levels that indicated a potential injury to the liver.

These risks may seem to be low, but during that time, there was no way to estimate the type of people who would develop DILI, rendering the medication unacceptably harmful. However, the novel polygenic risk score could help create liver organoids that display major risk variants to determine if a drug is dangerous before individuals ever take it.

What’s next?

In 2017, Takebe and collaborators showed how to create liver buds on a large scale; the study was published in the Cell Reports journal. Since then, the researchers have enhanced the process and reported success in 2019 in the Cell Metabolism journal at engineering liver organoids that model the disease.

But more studies involving a more diverse population is required to validate the preliminary discoveries and to scale up a DILI screening test for possibly extensive use, Takebe concluded.

Source:

Journal reference:

Koido, M., et al. (2020) Polygenic architecture informs potential vulnerability to drug-induced liver injury. Nature Medicine. doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1023-0.