A new study performed by scientists from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet Muenchen (LMU) has demonstrated that putatively immature dendritic cells in young children can trigger powerful immune responses. The findings may result in better vaccination protocols.

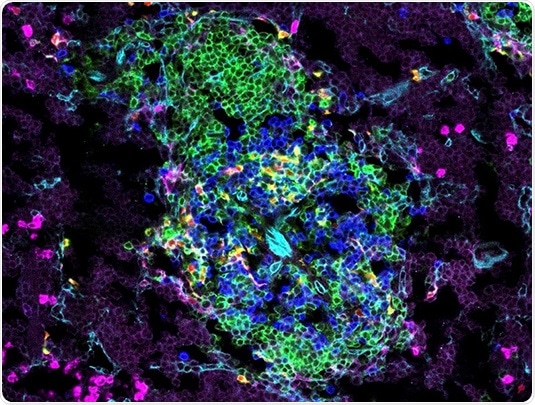

Dendritic cells (red/yellow) and T cells (blue) in the spleen of newborn, 8-day-old mice. Image Credit: Stephan Rambichler.

Dendritic cells are a crucial constituent of the inherent immune system, which represents the first line of defense of the body against tumor cells and infectious agents. The role of these cells is to stimulate the T-cell arm of the adaptive immune system, which imparts long-term and specific protection against viral and bacterial infections.

Proteins that alert the presence of invasive pathogens are engulfed and destroyed by dendrite cells. The ensuing fragments, or antigens, are shown on their surfaces. T cells that bear suitable receptors are subsequently activated to find and remove the pathogen.

Infants and young children have fewer numbers of dendritic cells than adults, and such juvenile cells also transport fewer numbers of antigen-presenting complexes on their surfaces. On the basis of these observations, immunologists have often believed that such cells are functionally immature.

But a new study published by a team of researchers, headed by Barbara Schraml, a Professor from LMU’s Biomedical Center, has demonstrated—utilizing the mouse as a model system—that such an assumption is actually inaccurate.

While early dendritic cells vary in their traits from those of mature mice, they can still induce effective immune reactions. The latest findings propose ways to increase the efficacy of vaccines for young children.

With the help of fluorescent tags bound to certain target proteins, Schraml and her collaborators traced the origins and biological traits of dendritic cells in both juvenile and newborn mice and compared them against mature animals.

Such studies demonstrated that dendritic cells are acquired from diverse source populations, based on the age of the animal taken into consideration. Dendritic cells found in neonatal animals grow from precursor cells created in the fetal liver. As the mice become older, these cells are gradually substituted by cells emerging from myeloid precursors—a group of white blood cells originating from the bone marrow.

However, our experiments demonstrate that—in contrast to the conventional view – a particular subtype of dendritic cells named cDC2 cells is able to activate T-cells and express pro-inflammatory cytokines in young animals. In other words, very young mice can indeed trigger immune reactions.”

Barbara Schraml, Professor, Biomedical Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet Muenchen

Nonetheless, early cDC2 cells vary in certain ways from those found in adult mice. For instance, the cells reveal age-dependent variations in the sets of genes expressed by them. It turns out that such variations reflect the fact that the cytokines or signaling molecules to which dendritic cells respond to change as the mice become older.

Among other things, the array of receptors that recognize substances which are specific to pathogens changes with age. Another surprise for us was that early dendritic cells activate one specific subtype of T-cells more effectively than others. Interestingly, this subtype has been implicated in the development of inflammatory reactions.”

Barbara Schraml, Professor, Biomedical Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet Muenchen

The study results represent a significant contribution to one’s interpretation of dendritic cell functions, and they could hold major implications for medical immunology. In newborns, their immune systems vary from those of more mature individuals, so much so that immune responses in early life are liable to be weaker than those stimulated later in life.

Our data suggest that it might be possible to enhance the efficacy of vaccinations in childhood by, for example, adapting the properties of the immunizing antigen to the specific capabilities of the juvenile dendritic cells.”

Barbara Schraml, Professor, Biomedical Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet Muenchen

Source:

Journal reference:

Papaioannou, N. E., et al. (2021) Environmental signals rather than layered ontogeny imprint the function of type 2 conventional dendritic cells in young and adult mice. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20659-2.