There are two phyla of tiny aquatic invertebrates: Kamptozoa and Bryozoa. They are related to ribbon worms (Nemertea), bristle worms, earthworms, and leeches (all of which are classified as annelids), as well as snails, clams, and other mollusks. Evolutionary biologists have never fully understood their exact location on the tree of life or how strongly related they are to these other animals.

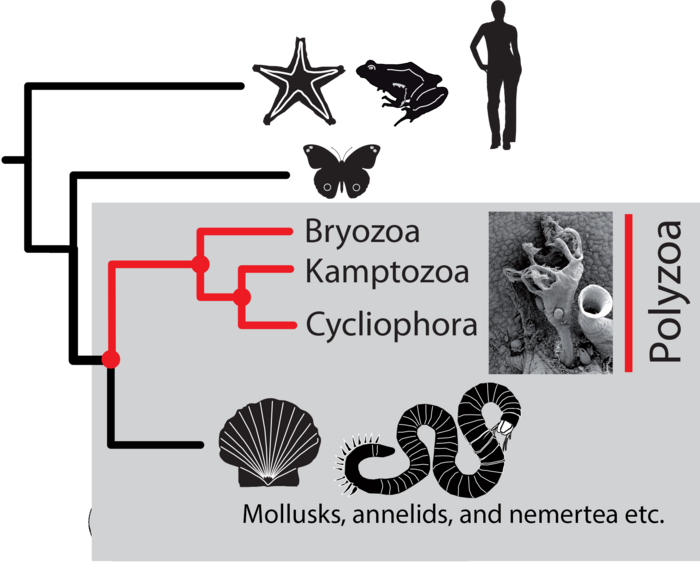

The evolutionary relationships of Kamptozoa and Bryozoa and their place on the tree of life have been revealed in this new study. The study found that they split from mollusks and worms earlier than expected and that they are part of a distinct group, called Polyzoa. Image Credit: Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology.

The evolutionary relationships of Kamptozoa and Bryozoa and their place on the tree of life have been revealed in this new study. The study found that they split from mollusks and worms earlier than expected and that they are part of a distinct group, called Polyzoa. Image Credit: Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology.

Prior research regularly shifted them about. Furthermore, even though Kamptozoa and Bryozoa were once thought to belong together, they were divided off based on how they looked and how they were built.

Now, researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), working with colleagues from St. Petersburg University and Tsukuba University, have shown that the two phyla split from mollusks and worms prior to previous studies had suggested, and thus they do in fact form a distinct group. They did this by using cutting-edge sequencing technology and potent computational analysis.

We’ve shown that by using high quality transcriptomic data we can answer a long-standing question to the best of our current techniques.”

Dr Konstantin Khalturin, Study First Author and Staff Scientist, Marine Genomics Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University

This research was published in the journal Science Advances.

The complete set of genetic data present in every cell is called a genome. It is further divided into genes. Each of these genes, which are composed of DNA base pairs and provide the instructions required to make a protein, contributes to the correct upkeep and care of a cell. The DNA must first be converted into RNA in order for the instructions to be carried out. The end result of this is a transcriptome, which is similar to a genome but recorded in RNA base pairs rather than DNA.

The genetic information varies depending on the species. Close relatives share a considerable deal of genetic information, but individuals separated by a higher evolutionary distance have more genetic distinctions. Researchers have increased the understanding of animal evolution by analyzing this data, but certain topics are still challenging to resolve.

Due to the strong relationship between Kamptozoa and Bryozoa and mollusks, annelids, and nemertea, minor errors in the dataset or missing data may cause an inaccurate placement on the evolutionary tree. Additionally, it is simple to pick up other creatures, such as algae that contaminate the sample when collecting these tiny critters.

Dr Khalturin emphasized that they took precautions to prevent contamination and afterward checked their dataset for RNA from algae and tiny animals to exclude any that could have originated from them.

The researchers sequenced the transcriptomes of two species of Bryozoa and four species of Kamptozoa in total, but with a much greater level of quality than had previously been possible. The transcriptome completeness in this study was above 96%, whereas previous datasets had completeness of 20–60%.

Researchers predicted proteins using these transcriptomes and compared them to data from 31 other species, some of which were closely linked to Kamptozoa and Bryozoa, such as clams and bristle worms, and others that were more distantly related, including frogs, starfish, insects, and jellyfish.

Scientists were able to compare several distinct genes and proteins at once because of the high-quality datasets. Dr Khalturin offered OIST’s excellent computing resources, which the researchers could use.

Our main finding is that the two phyla belong together. This result was originally proposed in the 19th century by biologists who were grouping animals based on what they looked like.”

Dr Konstantin Khalturin, Study First Author and Staff Scientist, Marine Genomics Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University

Dr Khalturin noted that the dataset may address other important evolutionary concerns, such as the precise position of mollusks and annelids on the tree of life and how life diversified, even if Khalturin claimed that this topic has now been solved to the best of his abilities.

Source:

Journal reference:

Khalturin, K., et al. (2022) Polyzoa is back: The effect of complete gene sets on the placement of Ectoprocta and Entoprocta. Science Advances. doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo4400.