Reviewed by Lauren HardakerAug 29 2025

When cells are harmed, they produce well-regulated responses that promote healing. These include a long-studied self-destruction mechanism that eliminates dead and damaged cells and a more recently discovered phenomenon that allows older cells to return to a younger state to aid in the regeneration of healthy tissue.

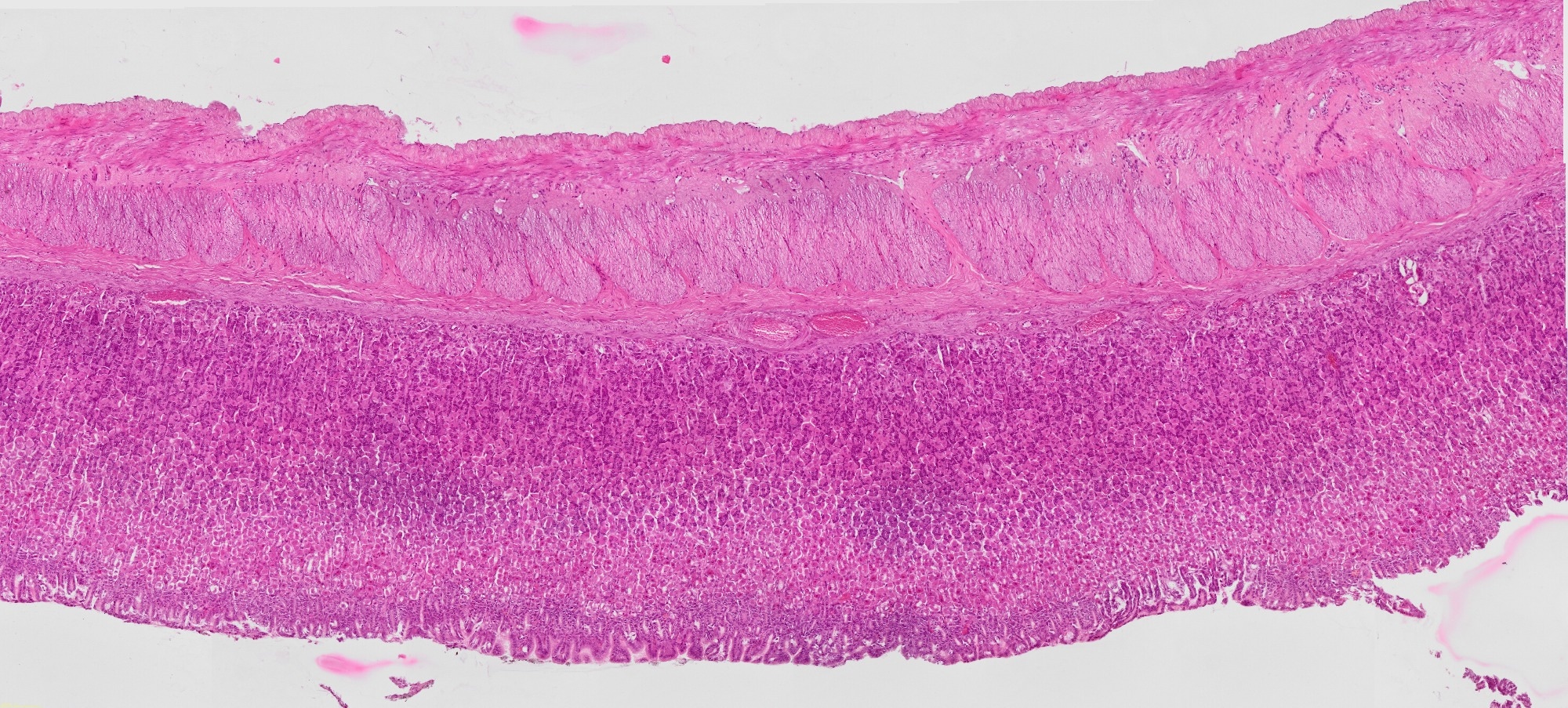

Image credit: micro.journey/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: micro.journey/Shutterstock.com

A new study in mice, headed by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Baylor College of Medicine, has discovered a previously unknown cellular purging mechanism that may help wounded cells revert to a stem cell-like state more quickly. The researchers named this newly found reaction cathartocytosis, derived from Greek root words meaning cellular cleansing.

The study, published online in the journal Cell Reports, employed a mouse model of stomach injury to reveal fresh insights into how cells repair, or fail to mend, in response to damage caused by infections or inflammatory diseases.

After an injury, the cell’s job is to repair that injury. But the cell’s mature cellular machinery for doing its normal job gets in the way. So, this cellular cleanse is a quick way of getting rid of that machinery so it can rapidly become a small, primitive cell capable of proliferating and repairing the injury. We identified this process in the GI tract, but we suspect it is relevant in other tissues as well.

Jeffrey W. Brown, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis

Brown compared the mechanism to "vomiting" or jettisoning garbage, which effectively provides a shortcut, allowing the cell to declutter and focus on regrowing healthy tissues faster than if it could only undertake a steady, controlled breakdown of waste.

As with many shortcuts, this one has possible disadvantages: According to the researchers, cathartocytosis is rapid yet messy, which may offer insight on how injury responses might fail, particularly in the context of chronic damage.

For example, persistent cathartocytosis in response to an infection indicates chronic inflammation and repeated cell damage, which is a breeding environment for cancer. According to the researchers, the festering mess of expelled cellular debris caused by cathartocytosis might potentially be used to diagnose or monitor cancer.

A Novel Cellular Process

The researchers discovered cathartocytosis inside a key regenerative injury response known as paligenosis, which was initially reported in 2018 by the present study’s principal author, Jason C. Mills, MD, PhD. Mills, who is now at Baylor College of Medicine, began this study as a faculty member in WashU Medicine’s Division of Gastroenterology. At the same time, Brown was a postdoctoral researcher in his lab.

Paligenosis occurs when injured cells move away from their regular functions and undergo reprogramming to an immature state, acting similarly to rapidly dividing stem cells during development. Initially, the researchers considered that decluttering cellular machinery in preparation for reprogramming occurs solely within cellular compartments known as lysosomes, where waste is destroyed in a slow and contained process.

However, the researchers spotted debris outside the cells almost immediately. They originally disregarded this as irrelevant, but Brown began to think that this was intentional when their early research revealed more external waste.

He used a mouse stomach injury model that caused mature cells to be reprogrammed to a stem cell state all at once, demonstrating that the “vomiting” reaction, which was now occurring in all stomach cells at the same time, was a feature of paligenosis rather than a bug. In other words, the vomiting process was not a random spill, but a newly discovered, normal way cells responded to harm.

Although the researchers identified cathartocytosis during paligenosis, they believe cells can use cathartocytosis to eliminate waste in other, more concerning scenarios, such as providing mature cells the ability to behave like cancer cells.

The Downside to Downsizing

While the newly discovered cathartocytosis process may help injured cells progress through paligenosis and regenerate healthy tissue more quickly, it also produces additional waste products that may fuel inflammatory states, making chronic injuries more difficult to resolve and increasing the risk of cancer development.

In these gastric cells, paligenosis — reversion to a stem cell state for healing — is a risky process, especially now that we’ve identified the potentially inflammatory downsizing of cathartocytosis within it. These cells in the stomach are long-lived, and aging cells acquire mutations. If many older mutated cells revert to stem cell states in an effort to repair an injury — and injuries also often fuel inflammation, such as during an infection — there’s an increased risk of acquiring, perpetuating and expanding harmful mutations that lead to cancer as those stem cells multiply.

Jason C. Mills, MD, PhD, Study Senior Author and Professor, Baylor College of Medicine

More study is needed, but the authors believe that cathartocytosis could perpetuate injury and inflammation in Helicobacter pylori infections in the gut. H. pylori is a type of bacterium that infects and damages the stomach, resulting in ulcers and raising the risk of stomach cancer.

The findings might potentially lead to novel treatment options for stomach cancer and possibly other GI cancers. Brown and WashU Medicine collaborator Koushik K. Das, MD, an associate professor of medicine, has produced an antibody that binds to elements of the cellular debris discharged during cathartocytosis. This allows them to identify when this process occurs, particularly in large numbers. In this sense, cathartocytosis might be employed as a marker of precancerous conditions, allowing for early diagnosis and treatment.

Brown added, “If we have a better understanding of this process, we could develop ways to help encourage the healing response and perhaps, in the context of chronic injury, block the damaged cells undergoing chronic cathartocytosis from contributing to cancer formation.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Brown, J. W., et. al. (2025) Cathartocytosis: Jettisoning of cellular material during reprogramming of differentiated cells. Cell Reports. doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.116070