Cell migration occurs throughout life as a response to internal and external signals, and can as such be indicative of changes occurring in the body. Imaging this movement and what processes control it can be critical in understanding cell behavior, development, and disease.

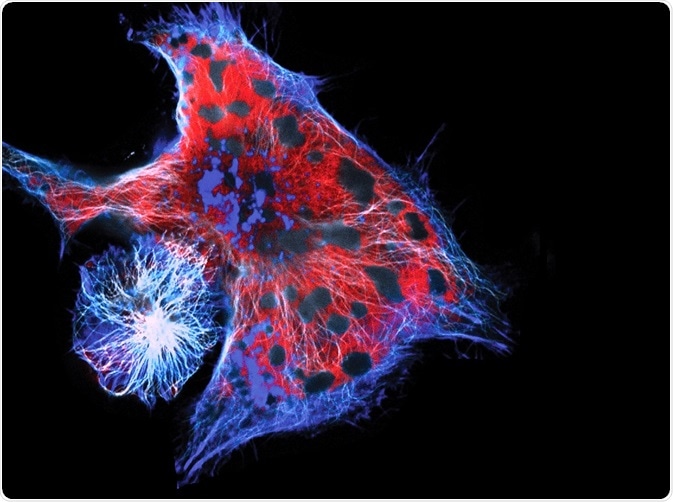

Image Credit: Vshivkova/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Vshivkova/Shutterstock.com

Why is Imaging Cell Migration of Interest?

Many processes occur before, during, or as a result of cell migration, both intracellularly and extracellularly. One important aspect, for example, is the dynamic assembly and disassembly of collagen matrices outside the cell.

Studies focusing on such structures have shown the dynamic nature and central role of the extracellular matrix during development and in critical life stages. In general, networks of biopolymers are central to cell migration and therefore often focused on in cell migration studies.

What are the Benefits of Confocal Reflection Microscopy?

The main advantage of confocal reflection microscopy, or CRM, over other microscopy techniques is that CRM captures cellular data in three dimensions over a given time. This allows important dynamic structures with specific spatial arrangements, such as fibrils and collagen, to be looked at with more spatial information than offered by other microscopy techniques. CRM has also been able to visualize the effects of cell migration, contraction of cells, and force exertion.

Many molecules, including collagen, are reflective to some extent. This is highly beneficial to observation by confocal microscopy, as it allows imaging without chemical processing, physical sectioning of the sample, or staining. The three-dimensional reconstruction is possible because images are taken at consecutive focal planes of the z-axis. Specific types of CRM, such as time-lapse CRM, allow for spatial and temporal visualization of collagen fibril formation and the assembly of the extracellular matrix as a result of cell migration.

Another benefit of CRM when looking at cell migration relates to the nature of extracellular matrices and cell cultures. Collagen matrices can be grown as cell cultures to be studied more closely in the laboratory, but are then often immersed in matrices with high water content and specific structural artifacts that are a result of specimen processing. CRM is capable of studying matrices in their hydrated state and does not require extensive manipulation of the sample.

However, the advantages of CRM are not universally agreed upon. For example, one study found that the orientation of fibers in the extracellular matrix can influence how well CRM detects them. If a fiber is at an angle of more than 50° from the imaging plane, the brightness decreases due to its vertical positioning and it remains undetected. The network structure that CRM catches, therefore, looks as if it is aligned with the imaging plane. The solution offered by this study was a different type of confocal microscopy: confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Applications

While it is a broad field, certain areas where CRM has been useful are highly notable. For example, as CRM in relation to collagen matrices has been discussed, CRM has successfully been used on collagen matrices from cell cultures and from interstitial samples to show they differ significantly in structural morphology and spatial organization. Time-lag CRM showed that interstitial extracellular matrices had a faster assembly rate, decreased lag phase, higher density, and slimmer diameter of collagen fibrils.

CRM has also been applied to cancer studies, where it has been used to study the migration of lung cancer cells. Such studies have shown, for example, that cancer cells immersed with commercially used extracellular matrix together with collagen have increased pore sizes and heterogeneity compared to cells that are not immersed in the matrix or are immersed in a lower quantity of matrix. Therefore, CRM shows that the extracellular matrix plays a critical role in the migration of cancerous cells, and collagen without extracellular matrix is not an environment that promotes cell migration.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 2, 2021