By Pooja Toshniwal PahariaReviewed by Lauren HardakerFeb 4 2026

By Pooja Toshniwal PahariaReviewed by Lauren HardakerFeb 4 2026Mouse gut experiments reveal why hypervirulent bacteria can quietly acquire drug resistance in the body, even when standard laboratory assays say the risk is low.

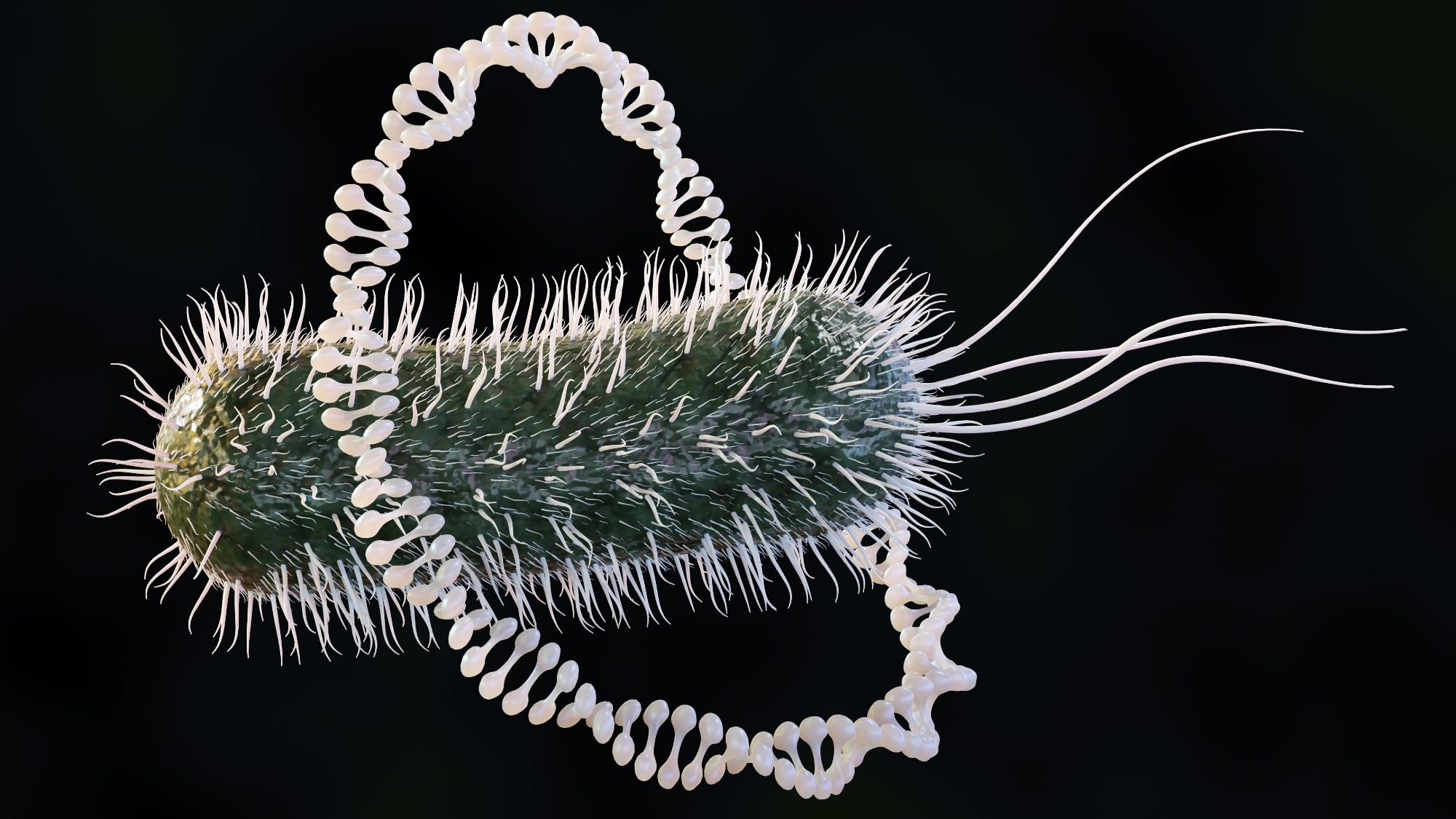

Image credit: Love Employee/shutterstock.com

Image credit: Love Employee/shutterstock.com

In a recent study published in Nature Communications, researchers investigated plasmid spread in the gut using a murine model colonized with hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp) and commensal Escherichia coli under antibiotic-perturbed conditions. The findings indicate that gut microenvironments, particularly anaerobic conditions, are a key determinant of plasmid transmission and help explain why laboratory assays can misrepresent in vivo behavior.

Notably, gut-enriched Incompatibility group P (IncP) Plasmid Taxonomic Unit (PTU)-P2 plasmids transferred more efficiently than related clades, highlighting how readily hvKp can acquire antimicrobial resistance (AMR) plasmids in host-associated gut settings. The findings highlight the growing risk of hypervirulent, drug-resistant strains emerging through plasmid acquisition rather than de novo resistance evolution.

Gut Conditions Reshape How Resistance Plasmids Actually Spread

Plasmids play a central role in the bacterial evolutionary landscape. They enable the rapid acquisition of various traits, including AMR, metabolic functions, and environmental adaptability. Classical studies of model plasmids have clarified fundamental mechanisms of plasmid biology. However, attention has increasingly shifted toward clinical plasmids, which are crucial for the global dissemination of AMR. This threat is especially pronounced among Enterobacterales, where Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli serve as major reservoirs of resistance genes.

Of particular concern is hvKp. It is increasingly acquiring multidrug-resistance plasmids, raising the risk of recalcitrant infections by hypervirulent organisms. This trend reveals critical gaps in understanding plasmid transmission in host-associated environments that are not captured by standard in vitro assays.

Mouse Gut Model Exposes Hidden Plasmid Transfer Dynamics

In the present study, researchers examined AMR plasmid spread in the gut, focusing on hvKp and IncP plasmid clades. Using a murine gut colonization model, they assessed plasmid transfer between hvKp SGH10 and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 strains under antibiotic-perturbed conditions that reduce colonization resistance and favor Enterobacterales expansion.

The researchers performed in vitro conjugation and plasmid stability assays to benchmark clinical carbapenemase plasmids, including pKPC2, against other resistance and laboratory plasmids. They used capsule-deficient and capsule-regulator mutants to evaluate the role of surface structures and mucoviscosity.

Subsequently, the team quantified plasmid transmission in vivo by orally inoculating mice with donor and recipient strains separated by a short temporal delay to confine conjugation to the gut, and enumerating donors, recipients, and transconjugants from stool samples collected over time. Bayesian regression modeling disentangled the relative contributions of primary and secondary plasmid transfer while accounting for population density effects.

To directly test secondary transfer, they engineered transfer-deficient pKPC2 variants by deleting the conjugation gene traF and restored conjugative function using chromosomally integrated mating genes, enabling controlled comparisons of transfer dynamics that isolate horizontal transfer from clonal expansion. Fluorescent tagging allowed spatial visualization of conjugation within distinct gut compartments.

The researchers performed large-scale genomic mining of public databases to assess the prevalence, taxonomic distribution, and evolutionary relationships of IncP plasmid clades. The findings informed the designation of human-associated, gut-linked clade II plasmids as PTU-P2 based on their overrepresentation in host-associated genomic datasets rather than direct environmental sampling.

Lastly, the team performed comparative conjugation assays under aerobic and anaerobic conditions to evaluate the influence of gut-like microenvironments on plasmid stability, fitness costs, and transmission efficiency.

Anaerobic Gut Favors Clinically Adapted Resistance Plasmids

The study revealed pronounced ecological specialization among broad-host-range IncP plasmids, with PTU-P2 plasmids transferring much more effectively in the mammalian gut than their closely related PTU-P1 plasmid counterparts. In mice, the clinically prevalent PTU-P2 plasmid pKPC2 markedly outperformed the environmental PTU-P1 plasmid RP4, despite similar conjugation efficiencies in standard aerobic laboratory assays. The findings suggest that subtle genetic differences can drive strong niche-specific adaptation that only becomes apparent under gut-like conditions.

Anaerobic conditions emerged as a key factor underlying this divergence. Under oxygen-depleted conditions that mimic the gut, PTU-P2 plasmids maintained high transfer rates, whereas PTU-P1 plasmids were severely impaired. These trends mirrored in vivo observations and help explain PTU-P2 plasmid enrichment in human-associated and clinical settings, in contrast to the largely environmental distribution of PTU-P1 plasmids. The authors note, however, that anaerobiosis likely acts alongside additional spatial and metabolic features of the gut, such as mucus architecture and nutrient gradients.

The hypermucoviscous capsule of hvKp posed a much weaker barrier to plasmid transfer in the in vivo environment than previously suggested by aerobic in vitro studies. Anaerobic growth significantly reduced capsule mucoviscosity without eliminating the capsule, facilitating donor-recipient interactions and comparable transfer between capsulated and non-capsulated strains in the gut, without implying loss of capsule-associated virulence traits.

Both experimental data and statistical modeling identified secondary transfer, where newly formed transconjugants act as donors, as essential for sustaining plasmid dissemination. Modeling indicated that transconjugant abundance best predicted subsequent increases in plasmid-bearing cells, and once established, transconjugant populations drove spread more effectively than continued input from the original donor strain. Targeted genetic experiments confirmed that clonal expansion alone could not account for these dynamics under the experimental conditions tested.

Genome-wide analyses reinforced these findings, revealing widespread global distribution of pKPC2-like PTU-P2 plasmids in human-associated bacteria, often carrying multiple resistance genes. In contrast, RP4-like PTU-P1 plasmids were rare in clinical niches. Together, the results highlight the role of gut microenvironments in shaping plasmid evolution and elevating the potential risk of hvKp infections by facilitating the emergence of hypervirulent, drug-resistant combinations.

Rethinking Resistance Risk Beyond Standard Laboratory Tests

The study findings demonstrate that microenvironmental factors, particularly anaerobic conditions, shape plasmid transmission in the gut by driving ecological specialization among IncP plasmids. Gut-enriched PTU-P2 plasmids, such as pKPC2, were transferred much more efficiently than PTU-P1 plasmids and were highly prevalent in human-associated bacteria, underscoring their clinical risk and explaining why laboratory-based assessments may underestimate this threat.

The study also revises the role of the hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule, showing that it presents only a modest barrier to gene exchange in vivo. Secondary transfer by transconjugants emerged as a key mechanism sustaining plasmid spread.

Because the experiments were conducted in antibiotic-perturbed mice, the authors caution that transfer rates may be lower in hosts with intact, complex microbiota and that the findings do not directly measure transmission events in patients. Future studies should explore these dynamics in more complex microbial communities to better predict and mitigate AMR dissemination.

Journal Reference

Yong, M., Low, W.W., Mishra, S. et al. (2025). Differential gut transmission of IncP plasmid clades involving hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae reveals plasmid-specific ecological adaptation. Nature Communications, 16, 11353. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66413-4. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66413-4