Retrotransposons, including LINE-1, Alu, SVA, and endogenous retroviruses, have reshaped the human genome by driving structural variation, regulatory innovation, and evolutionary expansion over millions of years. Although tightly controlled by epigenetic mechanisms, their continued activity influences development, immune signaling, aging, and disease, highlighting their dual role as both genomic architects and sources of instability.

Image credit: Tina Ji/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Tina Ji/Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Nearly half, and possibly more than two-thirds, of the human genome is composed of transposable elements (TEs), with retrotransposons being the only currently active mobile elements in humans. Retrotransposons are Class I elements that use a “copy-and-paste” mechanism, transcribe into ribonucleic acid (RNA), and reinsert into new genomic locations by reverse transcription. Once dismissed as “junk deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA),” they are now recognized as major contributors to genome architecture, regulatory innovation, and evolutionary change.1,3,4

This article examines how retrotransposons reshape gene regulatory networks, influence development and disease, and redefine our understanding of genome plasticity through evolutionary and modern genomic perspectives.

What Are Retrotransposons and How Do They Function?

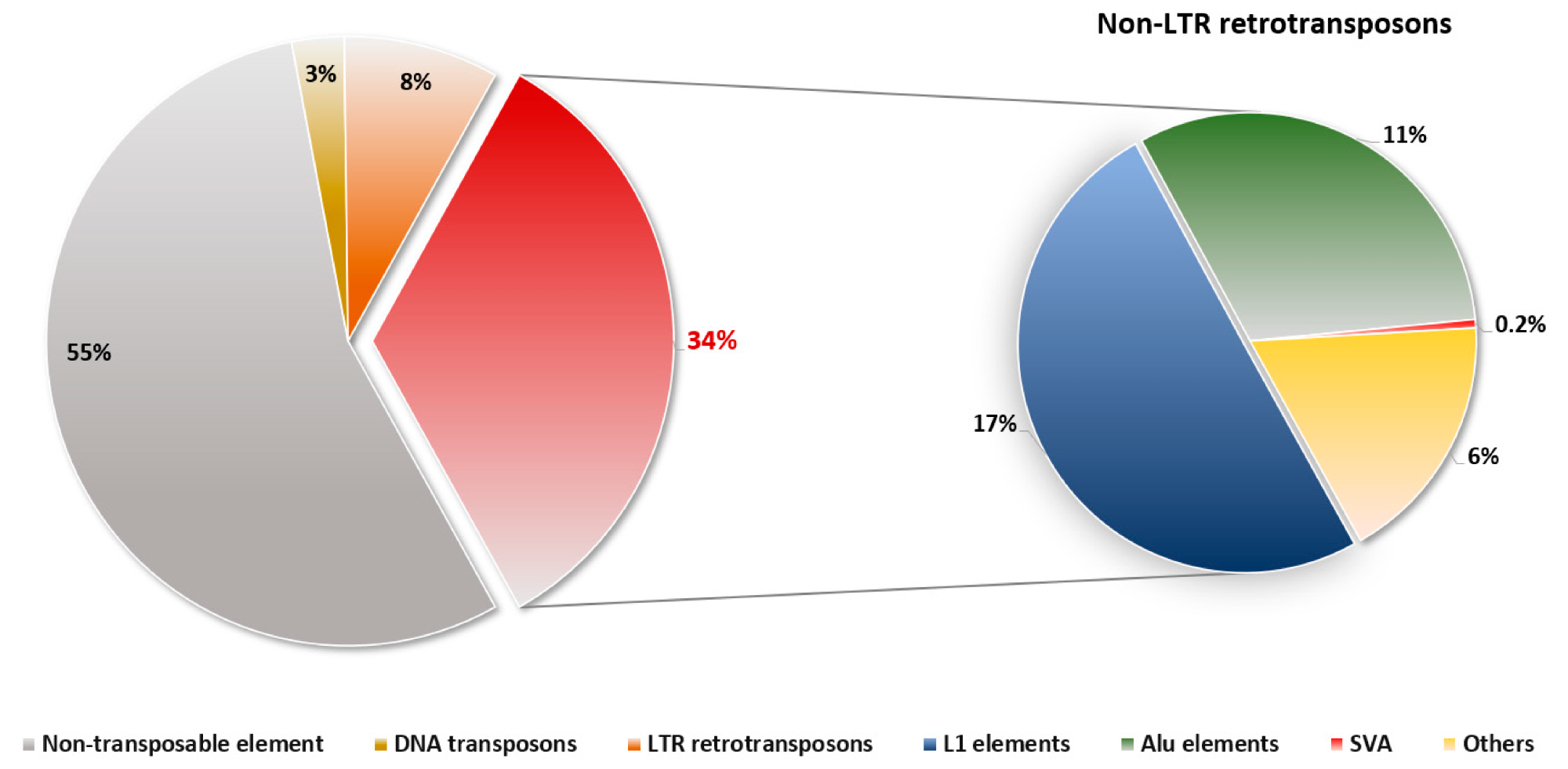

Retrotransposons are Class I transposable elements (TEs) that move within the genome through a copy-and-paste mechanism involving an RNA intermediate. They account for approximately 42-45 % of the human genome and are classified into two major groups: long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons and non-LTR retrotransposons.2

Composition of non-LTR retrotransposons in the human. Non-LTR retrotransposons constitute approximately 34 % of the entire human genome. A total of 17 % of L1 elements, 11 % of Alu elements, and 0.2 % of SVAs belong to non-LTR retrotransposons. As some of the elements are still active in humans, they cause genetic disorders and contribute to diversity.4

Composition of non-LTR retrotransposons in the human. Non-LTR retrotransposons constitute approximately 34 % of the entire human genome. A total of 17 % of L1 elements, 11 % of Alu elements, and 0.2 % of SVAs belong to non-LTR retrotransposons. As some of the elements are still active in humans, they cause genetic disorders and contribute to diversity.4

Non-LTR retrotransposons include long interspersed element-1 (LINE-1 or L1), short interspersed elements (SINEs) such as Alu, and SINE–variable number tandem repeat (VNTR)–Alu (SVA) elements. Of these, L1 is the only autonomous element, as it encodes the proteins required for its own mobilization, open reading frame 1 protein (ORF1p) and open reading frame 2 protein (ORF2p). In contrast, Alu and SVA elements are non-autonomous and rely on L1-encoded machinery for retrotransposition.2,4

Retrotransposition begins with transcription of the element into RNA, followed by translation and formation of ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs). After nuclear entry, the ORF2p endonuclease generates a single-stranded DNA nick at consensus sequences such as 5′-TTTT/AA-3′, and reverse transcription produces complementary DNA (cDNA) via target site-primed reverse transcription (TPRT), resulting in an insertion flanked by target site duplications.2,3

Full-length L1 elements are approximately 6 kb in length, contain a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) with promoter activity, two open reading frames, and a 3′ poly(A) tail, although most genomic copies are truncated and inactive.2,3

Retrotransposons and Human Genome Evolution

Non-LTR retrotransposons, particularly LINE-1, Alu, and SVA elements, have proliferated extensively during primate evolution and now account for roughly one third of the human genome. Their amplification over tens of millions of years has significantly contributed to genome expansion, adding hundreds of millions of base pairs to human DNA.4

The expansion of these elements follows a “master gene” model, in which a small number of highly active source elements drive the amplification of younger subfamilies. Retrotransposition has also produced insertion polymorphisms between individuals and species, generating structural variation that shapes the genome.4

Beyond simple copy number increases, retrotransposons promote genomic rearrangements through recombination between homologous elements, leading to deletions, duplications, inversions, and transductions of flanking sequences. They have fostered genetic innovation by mediating gene retrotransposition, exon shuffling, and exonization of embedded sequences.

Retrotransposon-mediated 3′ transduction events can mobilize adjacent genomic sequences to new loci, further diversifying gene structure. In some cases, retrotransposon-derived sequences have been co-opted into functional enhancers, promoters, and ultraconserved elements, illustrating an evolutionary trade-off in which genomic instability accompanies regulatory and gene innovation.1,4

Retrotransposons in Gene Regulation and Genomic Architecture

Retrotransposons play a substantial role in shaping gene regulation and genome architecture by donating intrinsic regulatory sequences and influencing chromatin organization. Their LTRs and internal promoters contain enhancer, promoter, splice, and polyadenylation signals that can be co-opted by host genes, thereby expanding transcription factor binding sites and rewiring tissue-specific regulatory networks. Genome-wide analyses indicate that a significant fraction of conserved regulatory regions and transcription factor binding sites derive from transposable elements.1,4

Host cells tightly control retrotransposons through epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications such as H3K9me3, and KRAB zinc-finger protein–KAP1/TRIM28–mediated repression complexes that establish heterochromatin and limit aberrant transcription.1,3 DNA methyltransferases, including DNMT1 and DNMT3A/3B, participate in maintaining transcriptional silencing of L1 and endogenous retroviruses.3

Retrotransposons are important for higher-order chromatin organization, with numerous CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) binding sites arising from TEs that contribute to chromatin looping and the three-dimensional (3D) genome structure.1

Want to save this for later? Click here to download your free PDF version.

Retrotransposons in Human Health and Disease

Retrotransposons are potent sources of genomic instability, capable of inducing insertional mutagenesis, double-strand breaks, and recombination-mediated rearrangements that contribute to diverse genetic diseases. More than 100 disease-causing de novo insertions of L1, Alu, or SVA elements have been documented in humans. Retrotransposon insertions have disrupted genes such as APC, contributing to tumorigenesis. Hypomethylation during cancer progression can reactivate LINE-1 expression, increasing somatic retrotransposition and tumor heterogeneity.1,3,4

Somatic retrotransposition has been reported in neuronal tissues and epithelial cancers, suggesting roles in mosaicism and tumor evolution.1,3 Importantly, retrotransposon RNA and cDNA intermediates can activate innate immune sensors and DNA damage responses, linking retrotransposon dysregulation to inflammation, autoimmunity, and aging-related processes. This dual nature underscores their role as both genomic parasites and contributors to adaptive cellular responses.3

Advances in Research and Emerging Frontiers

Technological advances have dramatically improved research on retrotransposons. High-throughput sequencing platforms such as Illumina enable detection of structural variation through short-read next-generation sequencing (NGS), while long-read technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) permit full-length resolution of insertions and complex rearrangements. Specialized computational tools leveraging split-read, discordant read-pair, and read-depth strategies have been developed to improve detection sensitivity for non-reference insertions.2

These advances have enabled large-scale mapping of polymorphic insertions, somatic events in cancer, and population-specific retrotransposon landscapes. As retrotransposons remain active and influence immune signaling, aging, and tumor biology, improved detection methods may support their use as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.2,3

Conclusions

Retrotransposons are no longer viewed as passive “junk DNA,” but as dynamic architects of the human genome. LINE-1, Alu, SVA, and endogenous retroviruses collectively account for a substantial fraction of genomic content and have shaped genome evolution over the past ~80 million years of primate history.4

By driving genome expansion, structural variation, regulatory innovation, and immune signaling, retrotransposons have profoundly influenced human biology. At the same time, their mobilization can induce genomic instability and disease. Ongoing advances in long-read sequencing, computational genomics, and epigenomic profiling continue to uncover their complexity, positioning retrotransposons at the forefront of precision genomics, evolutionary biology, and disease research.

References and Further Reading

- Mita, P., & Boeke, J. D. (2016). How retrotransposons shape genome regulation. Current opinion in genetics & development. 37. 90-100. DOI:10.1016/j.gde.2016.01.001, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2016.01.001

- Luqman-Fatah, A., Nishimori, K., Amano, S., Fumoto, Y., & Miyoshi, T. (2024). Retrotransposon life cycle and its impacts on cellular responses. RNA Biology. 21(1). 1048–1064. DOI:10.1080/15476286.2024.2409607, https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2024.2409607

- Cordaux, R., & Batzer, M. (2009). The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 10. 691–703. DOI:10.1038/nrg2640, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2640

- Lee, H., Min, J. W., Mun, S., & Han, K. (2022). Human Retrotransposons and Effective Computational Detection Methods for Next-Generation Sequencing Data. Life. 12(10). DOI:10.3390/life12101583, https://doi.org/10.3390/life12101583

Last Updated: Feb 19, 2026