Reviewed by Lauren HardakerJan 30 2026

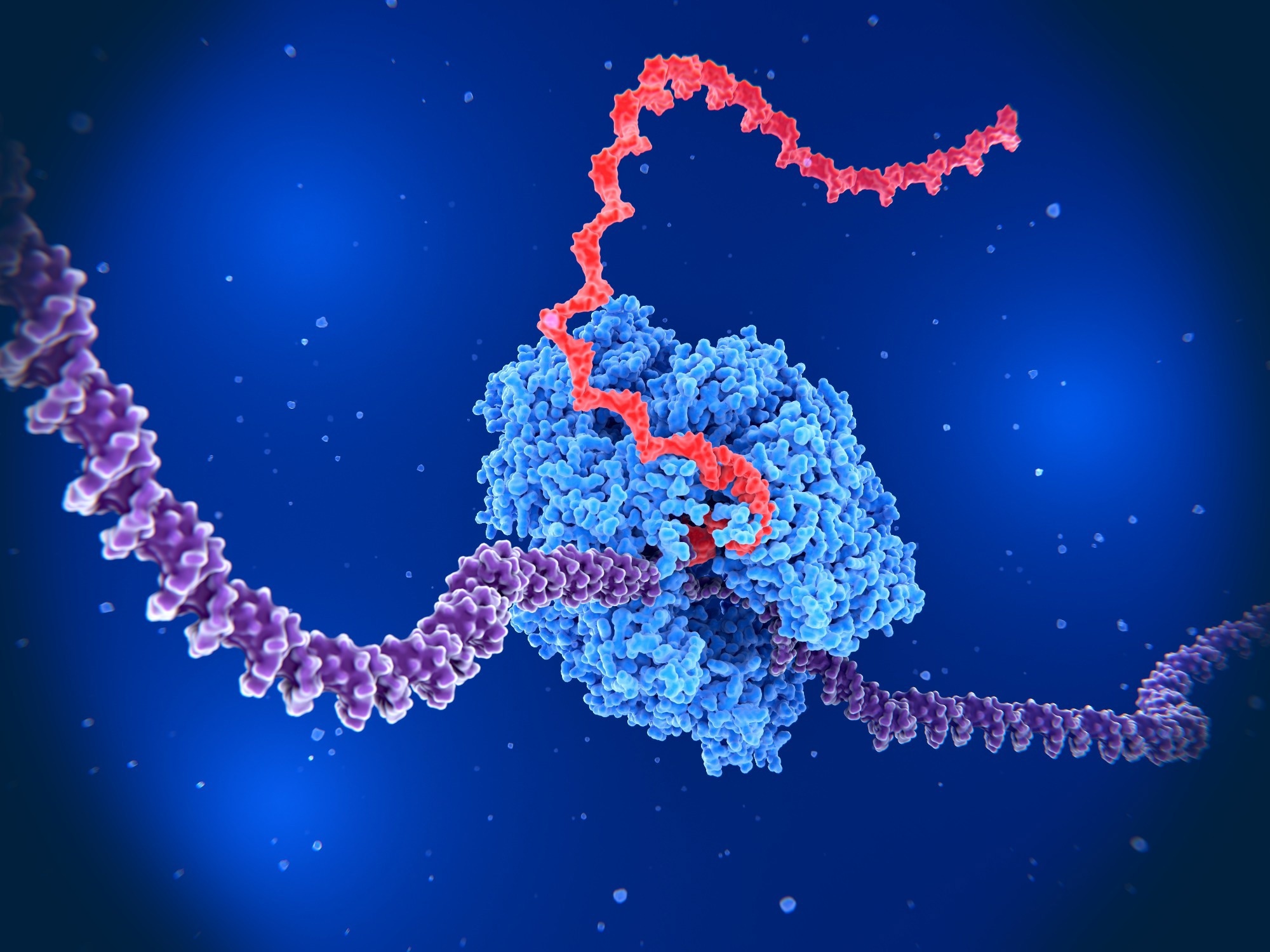

DNA can be regarded as an extensive library that contains all genetic information. Cells do not utilize this information simultaneously. Instead, they selectively copy only the necessary segments into RNA, which is subsequently employed to synthesize proteins, the fundamental building blocks of life. This copying mechanism, known as transcription, is performed by a molecule called RNA polymerase II.

Image credit: Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com

When RNA polymerase II initiates transcription of DNA, a specific site, Ser2, on its tail region is marked with a small chemical group, a phosphate. This phosphate serves as an indicator that transcription is underway. Detecting this indicator necessitated halting cellular activity and chemically treating the cells to visualize the phosphate. Therefore, it was not feasible to observe transcriptional dynamics in living cells.

The research team led by Professor Hiroshi Kimura at the Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) adopted an alternative strategy. Rather than freezing cells at a single point in time, they sought to monitor transcription continuously while maintaining cellular activity.

The team concentrated on a fluorescent protein known as a "mintbody," which was derived from an antibody that specifically binds to the phosphate marker that is present only during active transcription. Professor Kimura and colleagues successfully developed a mouse that expresses this mintbody throughout its entire body. They became the first in the world to directly visualize active transcription sites in cells of a living mouse.

Why This Matters

Transcription occurs continuously within the cell nucleus, similar to numerous lights flickering in a dark room. Using the mintbody mouse, the researchers detected hundreds to thousands of luminous dots, indicative of actively transcribing RNA polymerase II across nearly all tissues, including the brain, liver, and kidneys.

The quantity of glowing spots varied significantly based on the type of cell. For instance, T cells, which are immune cells that play a crucial role in protecting the body against viruses and abnormal cells, exhibited numerous bright signals. Neutrophils, another category of immune cells, showed considerably fewer signals. These variations clearly illustrate the extent to which each cell type transcribes genetic information in accordance with its specific function.

The researchers further noted that transcription is particularly vigorous in developing and differentiating cells, while it becomes considerably more stable in fully matured cells. In the testes, they were able to monitor dynamic transcriptional changes right up to the point where transcription nearly ceases during sperm development.

What is Next

This technology offers a robust new instrument for comprehending essential biological processes, including development and cell differentiation. By integrating this mouse with disease models, such as those related to cancer or aging, researchers can directly monitor the variations in transcription between healthy and diseased cells.

Furthermore, this methodology may provide a novel means to assess the impact of drugs on transcription, thereby paving the way for applications in drug discovery and immunology research.

Comment from the Researcher

Until now, most studies of transcription have focused on cultured cells. This research revealed that transcription in living tissues is far more diverse than we expected. Being able to directly observe genes at work allows us to capture concrete images of life processes that were previously inaccessible. Because this technology can be applied to many organisms, we believe it will greatly advance future research on transcription and gene expression.

Hiroshi Kimura, Professor, Cell Biology Center, Institute of Integrated Research, Institute of Science Tokyo