Reviewed by Lauren HardakerJan 23 2026

Researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine, using mouse models, reveal that oligodendrocyte precursor cells differentiate at a consistent, extensive rate throughout adulthood. Contrary to the long-held 'on-demand' theory, which suggests these cells only react to injury or aging, the study indicates that this regeneration is a continuous, intrinsic process.

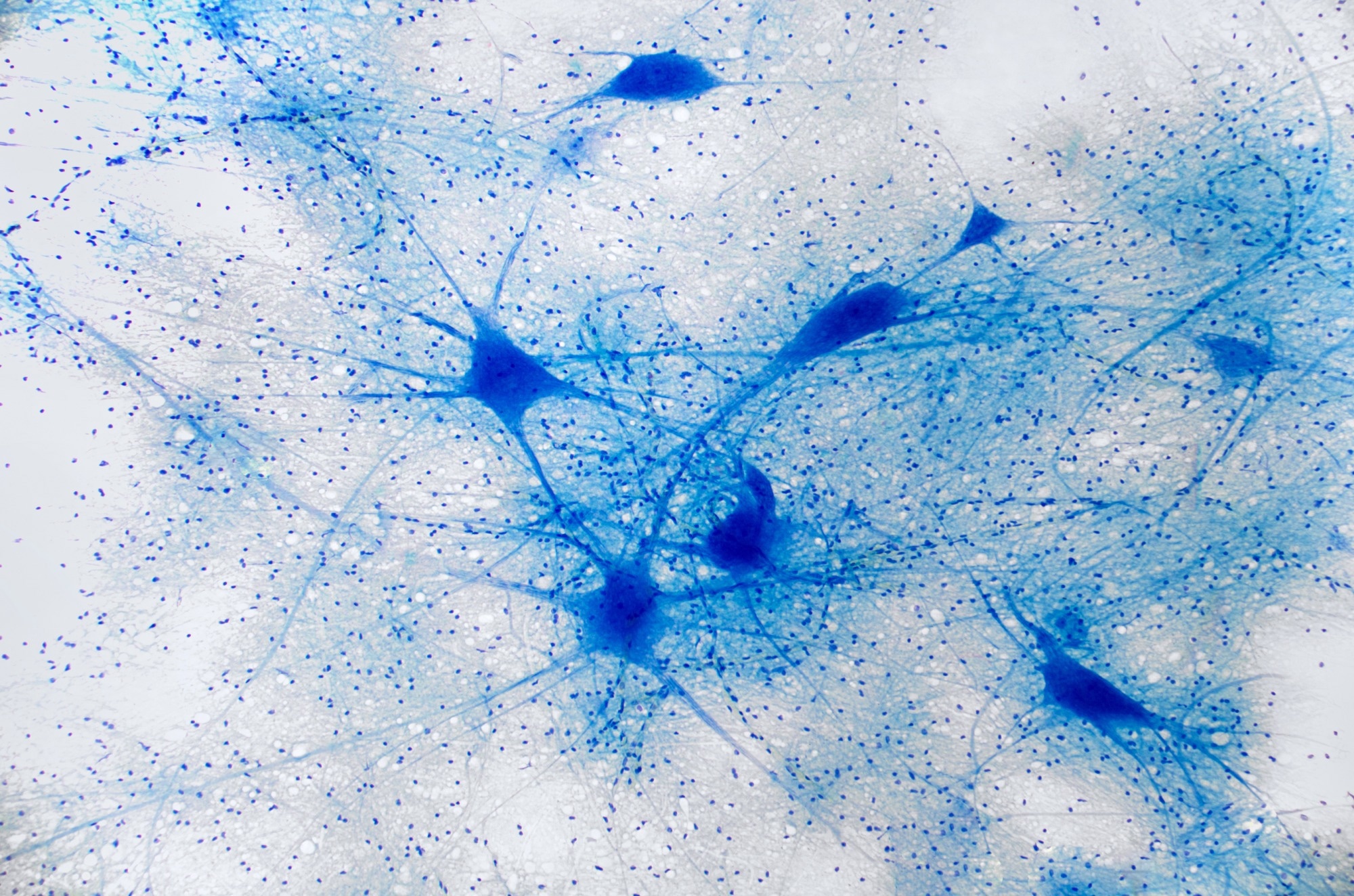

Image credit: peterschreiber.media/shutterstock.com

Image credit: peterschreiber.media/shutterstock.com

The study published in Science suggests that therapeutic strategies for multiple sclerosis could benefit from amplifying this natural, steady-state production of myelin.

These cells are responsible for producing a fatty-rich insulating layer called myelin, which encases nerve cell axons to facilitate the rapid transmission of electrical signals within the central nervous system.

Demyelinating disorders, typically resulting from autoimmune attacks, infections, or genetic predispositions, lead to a range of symptoms, including vision impairment, weakness, numbness, pain, and difficulties with coordination and balance in affected individuals.

In contrast to neurons, oligodendrocytes are generated over many decades within the human brain, facilitated by a group of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) that possess the ability to differentiate into new oligodendrocytes.

One of the reasons OPCs persist in the adult brain is because we need to make myelin for such a long time.

Dwight Bergles, Ph.D., the Diana Sylvestre and Charles Homcy Professor of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Due to OPCs' self-renewal capabilities, they are among the most persistent precursor cells in the nervous system.

In individuals suffering from multiple sclerosis, brain inflammation related to trauma, or other demyelinating conditions, myelin is removed.

“Loss of myelin disrupts the ability of nerve cells to transfer information and alters the function of neural circuits,” said Bergles.

The long-lasting natures of OPCs allow regeneration of oligodendrocytes and, at least partial, restoration of myelin.

The Johns Hopkins team examined the process by which OPCs differentiate into new oligodendrocytes. According to the researchers, this process is inefficient, as the majority of OPCs that attempt differentiation do not succeed in forming new oligodendrocytes.

The team investigated existing mammalian gene databases to identify a common molecular marker that could indicate when OPCs initiate their transformation into oligodendrocytes across various mammalian species, including mice, marmosets, and humans, to gain insight into the regulation of oligodendrocyte formation.

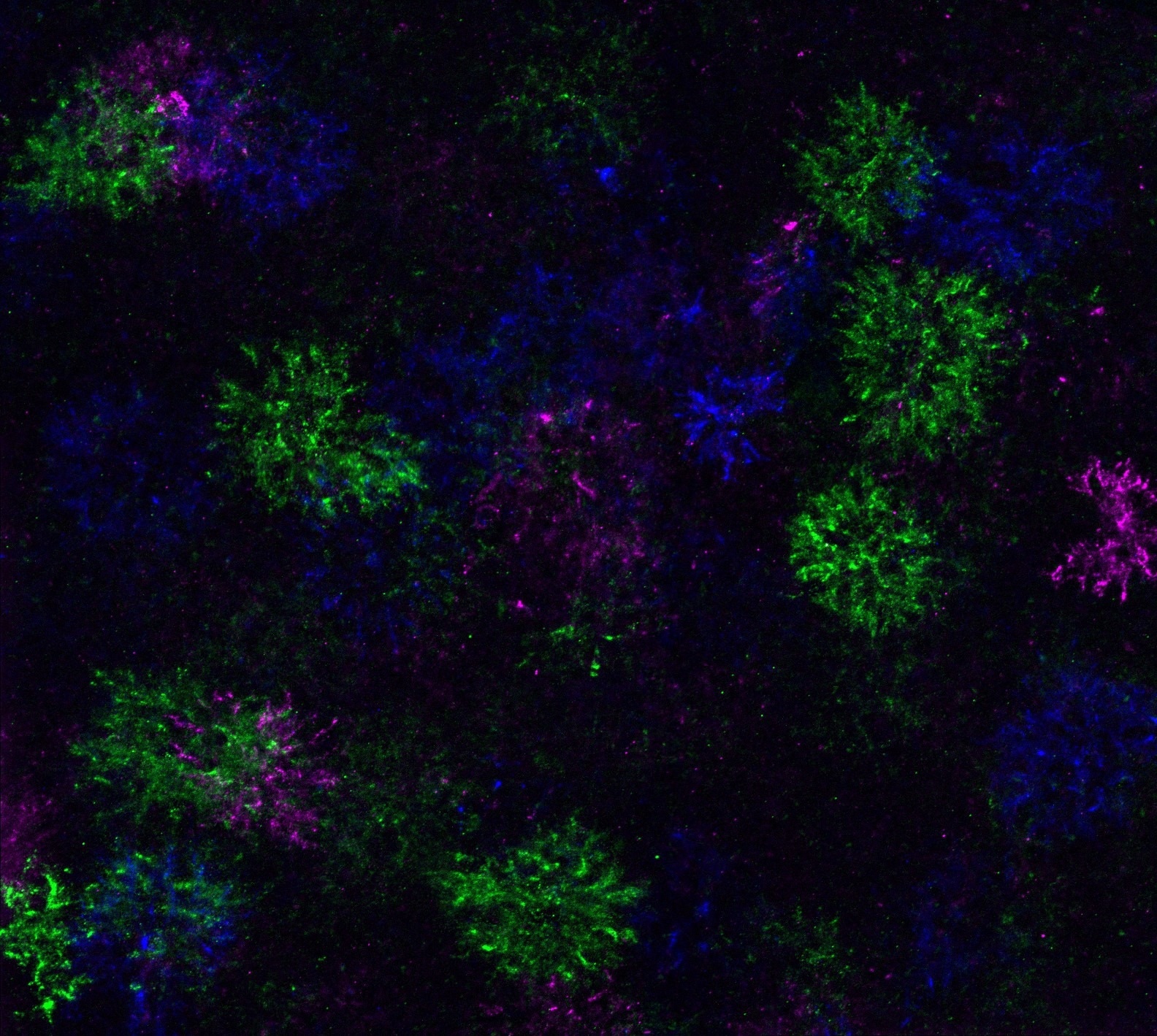

The team discovered that during the differentiation attempt, OPCs modify their gene expression to change the extracellular matrix, which is a type of protein meshwork that surrounds them. This molecular alteration led to the emergence of structures resembling “dandelion clocks,” or DACS, named for their resemblance to the spherical seed head of a dandelion, particularly during OPC differentiation. This discovery provided a novel method for monitoring OPC differentiation in the brain.

“Dandelion clock-like structures,” or DACS, formed when oligodendrocyte precursor cells attempt to differentiate. Image Credit: Yevgeniya Mironova, Ph.D

“Dandelion clock-like structures,” or DACS, formed when oligodendrocyte precursor cells attempt to differentiate. Image Credit: Yevgeniya Mironova, Ph.D

The research team successfully tracked DACS in the brains of mice, employing genetic labeling and imaging techniques to confirm that each differentiating OPC generates a DACS that remains until the precursor cells develop into oligodendrocytes.

With the introduction of this new tracking tool, the scientists reported experiencing a eureka moment upon discovering that OPCs were trying to differentiate in all areas of the mouse brain, including regions devoid of oligodendrocytes and lacking myelination of neurons.

It showed us that OPC differentiation was constantly happening all over the brain. They seem to have this intrinsic drive to continually try to make new oligodendrocytes. Although this may seem very inefficient, we think this process evolved to provide equal potential to make new oligodendrocytes and myelin anywhere in the brain. It is then left to the neurons to help decide which of these differentiating cells survives to make myelin.

Dwight Bergles, Ph.D., the Diana Sylvestre and Charles Homcy Professor of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

The researchers removed oligodendrocytes and myelin from mouse brains to imitate conditions related to myelin diseases, damage, and aging. Surprisingly, they discovered that OPCs continued their normal differentiation process, irrespective of the immediate necessity for new myelin.

While there was no rise in OPC differentiation, a greater number of these cells persisted to generate new oligodendrocytes, indicating that alterations in integration, rather than the direct activation of precursor cells, account for the observed increase in the formation of new myelin following injury.

It seems that this constant OPC differentiation was designed for brain development, not for repair.

Dwight Bergles, Ph.D., the Diana Sylvestre and Charles Homcy Professor of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Bergles suggests that finding treatments that harness the developmental aspects of the oligodendrocyte production process may increase the chances of rapid myelin repair.

Source:

Journal reference:

Mironova, A. Y., et al. (2026) Myelin is repaired by constitutive differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.adu2896. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adu2896