Reviewed by Lauren HardakerFeb 20 2026

Imagine balancing a ruler upright in the palm of your hand: you need to continually monitor its angle and make several small movements and changes to keep it from tipping over. It would take a lot of practice to master this.

Image credit: Sinhyu Photographer/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Sinhyu Photographer/Shutterstock.com

Variable Stiffness of a Tactile Hair

In engineering, this is known as the “inverted pendulum” or “cart-pole” issue, in which a control system learns to balance an upright pole attached to a rolling cart. This issue is used as a benchmark in fields such as robotics, control theory, and artificial intelligence to determine if a control system can adapt and respond to information in a meaningful way. It's significant even in the earliest days of life. Every human child must solve a challenge similar to this before becoming a toddler.

Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, trained brain organoids, which are small fragments of brain tissue generated in a laboratory, to answer this fundamental benchmark problem. Using electrical impulses to send and receive information from the organoids, the researcher’s software trained the lab-grown brain tissue to continually perform significantly better on the cart-pole challenge. The findings are presented in a study published in Cell Reports.

The outcomes of this study are fundamental to science and health research, as it seeks to understand how information is communicated in the brains of complex organisms through the electrical spiking of neurons, enabling them to learn and perform tasks more effectively.

This new tool could provide new insights for researching how neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, stroke, concussions, autism, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, dyslexia, and ADHD can alter or impair the brain’s ability to learn could be found in the increasing knowledge of how complex neural circuits work and adapt.

We’re trying to understand the fundamentals of how neurons can be adaptively tuned to solve problems. If we can figure out what drives that in a dish, it gives us new ways to study how neurological disease can affect the brain’s ability to learn.

Ash Robbins, PhD Student, Baskin School of Engineering Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California, Santa Cruz

This study represents the first rigorous academic demonstration of goal-directed learning in lab-grown brain organoids, laying the groundwork for adaptive organoid computation, which investigates the ability of lab-grown brain organoids to learn and solve tasks.

These are incredibly minimal neural circuits. There’s no dopamine, no sensory experience, no body to sustain, no goals to pursue. And yet, when given targeted electrical feedback, this tissue is plastic enough and structured enough to be pushed toward solving a real control problem. That tells us something important: the capacity for adaptive computation is intrinsic to cortical tissue itself, separate from all the scaffolding we usually assume is necessary.

Keith Hengen, Associate Professor, Biology, Washington University in St. Louis

Organoid Coaching

Organoids, which are heart, liver, lung, brain, and other tissues generated in the lab from stem cells, have been widely employed in biomedical research over the past 15 years, but researchers are just now beginning to investigate how they can be used to understand how brains learn.

Brain organoids simulate early brain development, structure, and function. They are smaller than a peppercorn but may include a network of several million neurons, which are brain cells that send electrical messages throughout the body. Researchers can monitor neurons firing within organoid tissue and induce specific neurons to activate by putting the organoids on a customized chip.

From an engineering perspective, what makes this powerful is that we can record, stimulate, and adapt in the same system. This is not just recording neural activity. It is a closed-loop bioelectrical interface where the tissue’s response directly shapes its next input. That is what allows us to study learning as a physical process, which has been very difficult to study directly in intact brains.

Mircea Teodorescu, Professor, Baskin School of Engineering Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California, Santa Cruz

The team aimed to see whether organoid neurons could do the cart-pole task, drawing on Steve Potter's decades-old work at Caltech and Georgia Tech.

The researchers employ electrical simulation to transmit and receive information to and from neurons using organoids made from mouse stem cells and an electrophysiology device created by industry partners Maxwell Biosciences.

They communicate the angle of the pole, located in a virtual environment, to the organoid by sending stronger or weaker impulses in either direction. The researchers apply the force to the virtual pole after seeing how the organoid transmits information about how to apply force to balance the pole.

In their pole-balancing experiments, the researchers monitor the organoid controlling the pole until it drops, which is known as an episode. The pole is then reset to start a fresh episode. In essence, the organoid engages in a video game in which the objective is to keep the pole upright for as long as possible.

The researchers track the organoid's progression in five-episode intervals. If the organoid has kept the pole upright for longer, on average, in the last five episodes than in the previous 20, it does not receive a training signal because it has improved. If it does not increase its average time keeping the pole upright, it is given a training signal.

The organoid does not get training input while balancing the pole; instead, it receives it at the end of each episode. Reinforcement learning is an AI method that determines which neurons within the organoid receive the training signal.

Robbins added, “You could think of it like an artificial coach that says, ‘you’re doing it wrong, tweak it a little bit in this way. We’re learning how to best give it these coaching signals.”

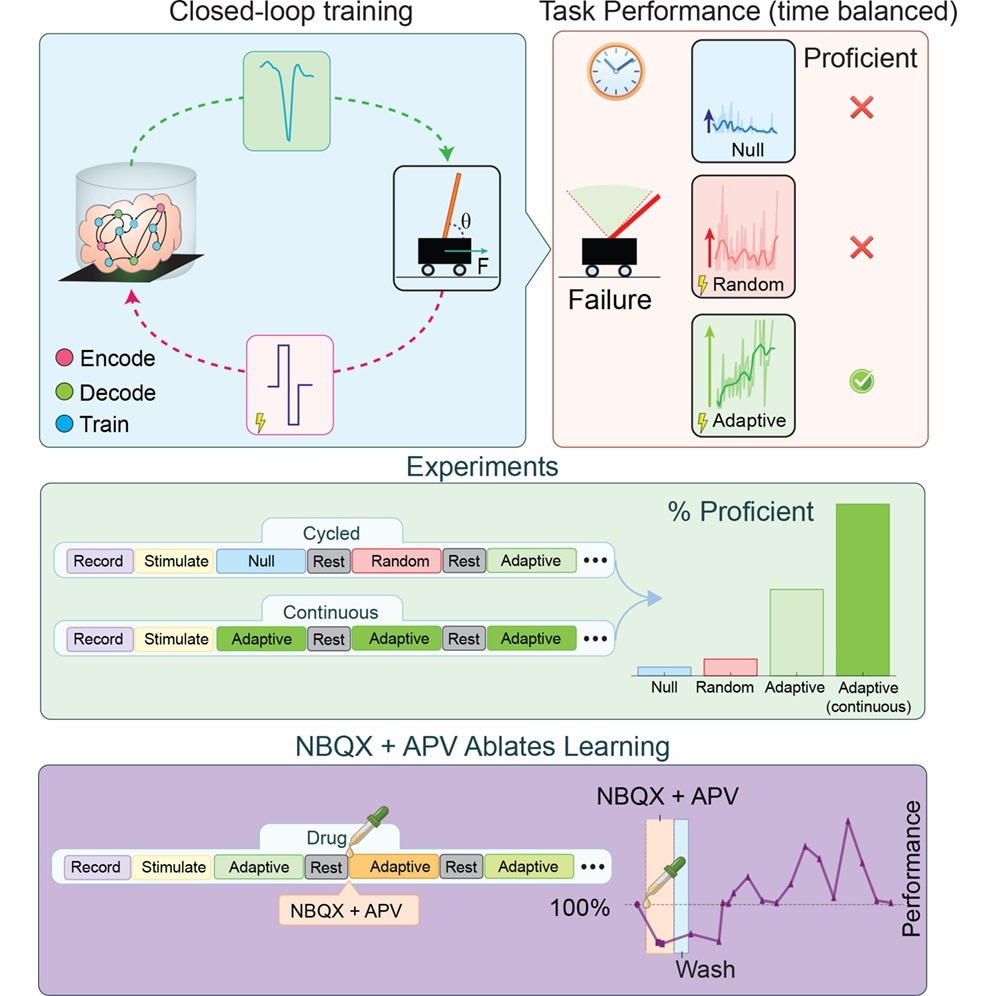

Experimental overview for in vitro learning

Experimental overview for in vitro learning

Observing Improvement

The study's findings show that the reinforcement learning algorithm may train brain organoids to improve their performance in the cart-pole challenge, enabling them to balance the pole for longer periods.

The researchers used a strict success framework to ensure they were seeing actual progress rather than random success, including a threshold for the least amount of time an organoid needed to balance the pole to "win" the game.

They discovered that employing their coaching approach resulted in much superior performance compared to organoids trained at random, with a 4.5% "winning" percentage for random training and a 46 % winning rate for adaptive training with reinforcement learning.

“When we can actively choose training stimuli, we can actually shape the network to solve the problem. What we showed is short-term learning, in that we can take an organoid in one state and shift it into another one that we’re aiming at, and we can do that consistently,” Robbins stated.

However, the organoids appear to "forget" most of what they have learned after prolonged inactivity. After 15 minutes of balancing the pole in many episodes, the organoid takes a 45-minute break. The researchers discovered that after this rest time, the organoid's performance returns to baseline, showing that it does not maintain its training.

Haussler suggested that using more complex organoids may help overcome this lack of recall.

“It is likely that more sophisticated organoids, perhaps grown to include multiple brain regions involved in animal learning, will be needed to recapitulate the kind of long-term adaptive performance improvement we see in animals. We’ll see,” Haussler noted.

The researchers want to understand why their coaching approach works, including which neurons to target, which training signals are most effective, and how long-term learning occurs.

Robbins made this possible by creating BrainDance, an open-source software tool that supports these experiments. To increase participation in organoid research and advance the field, the technology is made so that anyone with the biological know-how to cultivate brain organoids can perform neural simulation learning experiments and evaluate the outcomes without having to write code for a game, hardware interface, or training environment.

Robbins further stated, “This software makes running really complicated experiments extremely easy. Usually labs spend years building up all of this kind of software themselves. Now, any biologist could download our software very easily and run these types of experiments in just minutes.”

“Ash’s software could build a larger community around adaptive organoid computation. But we want to make it clear that our goal is to advance brain research and the treatment of neurological diseases, not to replace robotic controllers and other kinds of computers with lab-grown animal brain tissues. The latter might be considered cool, but would bring up serious ethical issues, especially if human brain organoids were used,” Haussler concluded.

Source:

Journal reference:

Robbins, A., et.al. (2026) Goal-directed learning in cortical organoids. Cell Reports. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2026.116984. https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(26)00062-8.