Reviewed by Lauren HardakerOct 8 2025

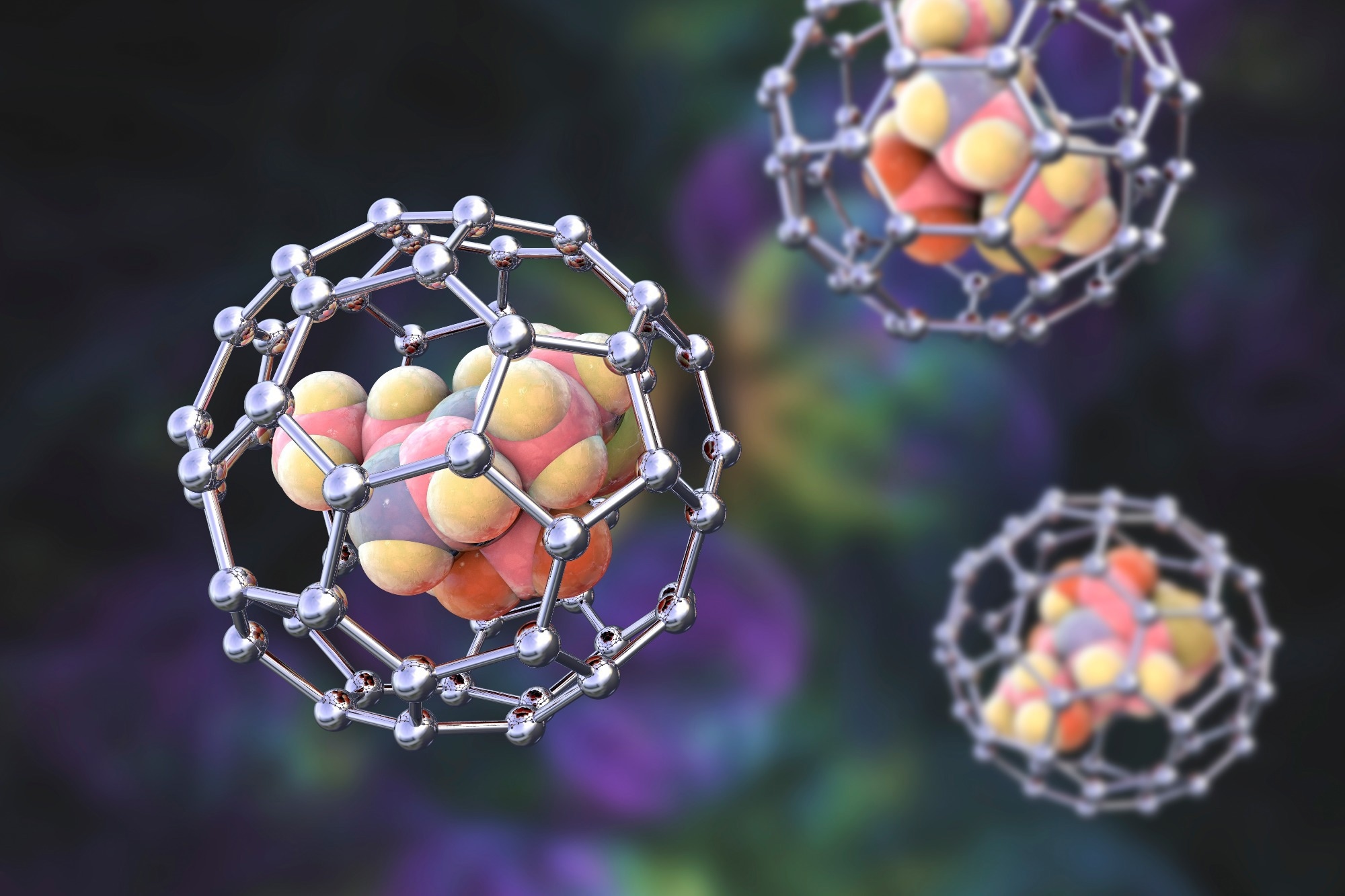

Abdominal pain is common in various digestive diseases, including inflammatory and irritable bowel syndrome. To develop targeted treatments for stomach discomfort, scientists uncovered a new enzyme in gut bacteria and are employing nanoparticles to transport drugs inside cells.

Image credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Currently, there are no specific treatments for gut pain, and conventional pain relievers are frequently insufficient to manage symptoms. Opioids, NSAIDs, and steroids all have side effects, some of which are directly harmful to the digestive system.

Two recent studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and Cell Host & Microbe focused on PAR2, a receptor implicated in pain signaling that has been linked to gastrointestinal diseases marked by inflammation and pain. A promising target for the treatment of gut pain, PAR2 is found on the lining of the gut and on pain-sensing nerves in the gut. It is activated by specific enzymes known as proteases.

In focusing on this receptor, we’ve mapped out a pathway between a bacterial enzyme and pain and determined how to block PAR2 using nanoparticles—both of which may help us to treat pain related to digestive disorders in the future.

Nigel Bunnett, Professor and Chair, Department of Molecular Pathobiology, New York University

He is also a faculty member in the NYU Pain Research Center.

A Brand-New Bacterial Enzyme as a Regulator for Pain

Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the composition of microbes in the gut, contributes to many digestive diseases. Scientists are increasingly interested in how microbiome-targeted medicines, such as probiotics, can help restore the balance of good and bad bacteria.

Bacteria in the gut use a variety of amino acids and other tiny metabolites to interact with the rest of the body. Matthew Bogyo, a pathology, microbiology, and immunology professor at Stanford University School of Medicine, wanted to know if bacteria communicated by creating proteases and if these enzymes affect PAR2 activity, which could be a factor in pain.

Bogyo and his colleagues tested a large library of human gut bacteria strains to see if they produced enzymes capable of cleaving and activating PAR2. Surprisingly, over 50 bacteria produced enzymes that cleaved PAR2.

The researchers focused on a previously unknown enzyme produced by a rod-shaped bacterium called Bacteroides fragilis (B. fragilis), which exhibited exceptionally high activity. B. fragilis is often found in the human colon; however, there is some evidence that it contributes to inflammatory bowel disease.

B. fragilis a sleeping pathogen of sorts. It’s an organism that can hang out in the gut without doing any damage, but under certain conditions, it can cause problems. One of the ways it may be doing that is through regulating signals that it sends to the host.

Matthew Bogyo, Professor, School of Medicine, Stanford University

Bogyo, in cooperation with Bunnett, discovered that the enzyme generated by B. fragilis cleaves PAR2 to activate the receptor. In subsequent cell and mouse studies, the researchers compared conventional B. fragilis bacteria to a modified variant of the bacterium in which the enzyme had been deleted.

They discovered that the protease produced by B. fragilis bacteria activated neurons that sense and transmit pain, damaged the intestinal barrier, and caused inflammation and pain in the colon.

“The results were black and white: if the protease was present, there was pain signaling, and if the protease was not present, there was no pain signaling. Our study identifies a new axis of communication between gut bacteria and the host that has implications for how symptoms may be triggered in inflammatory bowel disease,” added Bogyo.

“There has been a lot of work to describe changes in the microbiome that could be associated with disease, but this study is among the first to look at the role of proteases in this pathway,” further added Bunnett.

The researchers, who recently published their findings in Cell Host & Microbe, believe the newly found B. fragilis enzyme could be used to treat unpleasant digestive diseases by blocking the enzyme and deactivating its signaling system.

Using Nanoparticles to Reach a Moving Target

In a separate study published in PNAS, researchers attempted to take advantage of a known PAR2 behavior: when activated, the receptor travels from the surface of gut cells to compartments within the cells known as endosomes.

The receptor continues to function inside endosomes, causing inflammation and discomfort by activating nerve cells and breaking down the protective barrier of cells that line the intestines.

If this receptor internalizes and signals from these compartments, we have to develop a drug delivery strategy that will target the receptor inside the compartments.

Nigel Bunnett, Professor and Chair, Department of Molecular Pathobiology, New York University

To get the drug inside endosomes, the researchers used nanoparticles, tiny, spherical vehicles that can encapsulate drugs and transport them into cells. Nanoparticles are used to precisely direct drugs, for example, targeting tumors in cancer treatment while sparing healthy tissue, reducing side effects and drug dosage.

This method could be especially useful in digestive diseases, as nanoparticles can deliver drugs to the gut wall without spreading to other parts of the body.

To test this method, the researchers utilized AZ3451, an investigational drug that inhibits PAR2. They encapsulated AZ3451 in two types of nanoparticles that target the two main receptor signaling locations that cause stomach pain: epithelial cells lining the intestine and nerve cells. The nanoparticles were designed to release the medicine slowly over several days.

“That sustained release is exactly what you want for a chronic disease,” noted Bunnett.

In cellular studies, scientists discovered that the nanoparticle-delivered medication was considerably more effective at inhibiting PAR2 signaling in epithelial and nerve cells than the drug on its own. In other experiments on mice with inflammatory bowel disease, administering nanoparticles containing AZ3451 reduced pain-like behaviors, whereas the drug alone was essentially ineffective.

“Using nanoparticles for drug delivery demonstrates a precision-targeted approach. These nanoparticles are precisely directed not only to a particular cell, but a particular compartment within the cell and a particular receptor within the compartment,” added Bunnett.

Source:

Journal references:

Teng, S. L. et al. (2025) Nanomedicines targeting protease-activated receptor 2 in endosomes provide sustained analgesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2412687122

Lakemeyer, M. et al. (2025) A Bacteroides fragilis protease activates host PAR2 to induce intestinal pain and inflammation. Cell Host & Microbe. doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2025.09.010