By Pooja Toshniwal PahariaReviewed by Lauren HardakerJan 14 2026

By Pooja Toshniwal PahariaReviewed by Lauren HardakerJan 14 2026A newly discovered giant virus from a Japanese pond rewrites what scientists thought they knew about how massive DNA viruses infect cells, reshape their hosts, and evolve new ways to replicate without destroying them.

Image credit: Jake Pixo/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Jake Pixo/Shutterstock.com

In a recent study published in the Journal of Virology, researchers describe the discovery of a novel giant virus, termed ushikuvirus, identified in a freshwater pond located in Ibaraki Prefecture near Tokyo, Japan.

A Freshwater Giant Virus with Unusual Nuclear Effects

Described as a newly identified clandestinovirus-like giant virus, ushikuvirus infects Vermamoeba vermiformis and possesses a large genome of at least 666 kilobase pairs (kbp). Despite sharing genomic similarities with known giant viruses, ushikuvirus exhibits distinctive structural features and cytopathic effects (CPE), including host cell enlargement, cell rounding, and nuclear membrane disruption, offering new insights into giant virus evolution and host–pathogen interactions.

Giant double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) viruses represent a rapidly expanding and evolutionarily intriguing group of viruses that infect eukaryotes. Since the discovery of Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus in 2003, numerous giant viruses have been recovered from aquatic and terrestrial environments worldwide.

Among these, the family Mamonoviridae, established in 2023, includes three medusavirus species that infect Acanthamoeba. A closely related virus, clandestinovirus, identified in 2021, infects Vermamoeba vermiformis and shares key genomic features, including nuclear replication and histone encoding. The recent identification of ushikuvirus, which is closely related to but distinct from both clandestinovirus and Mamonoviridae, further extends understanding of giant virus diversity and evolution.

Multimodal Imaging and Genomics Reveal Ushikuvirus Biology

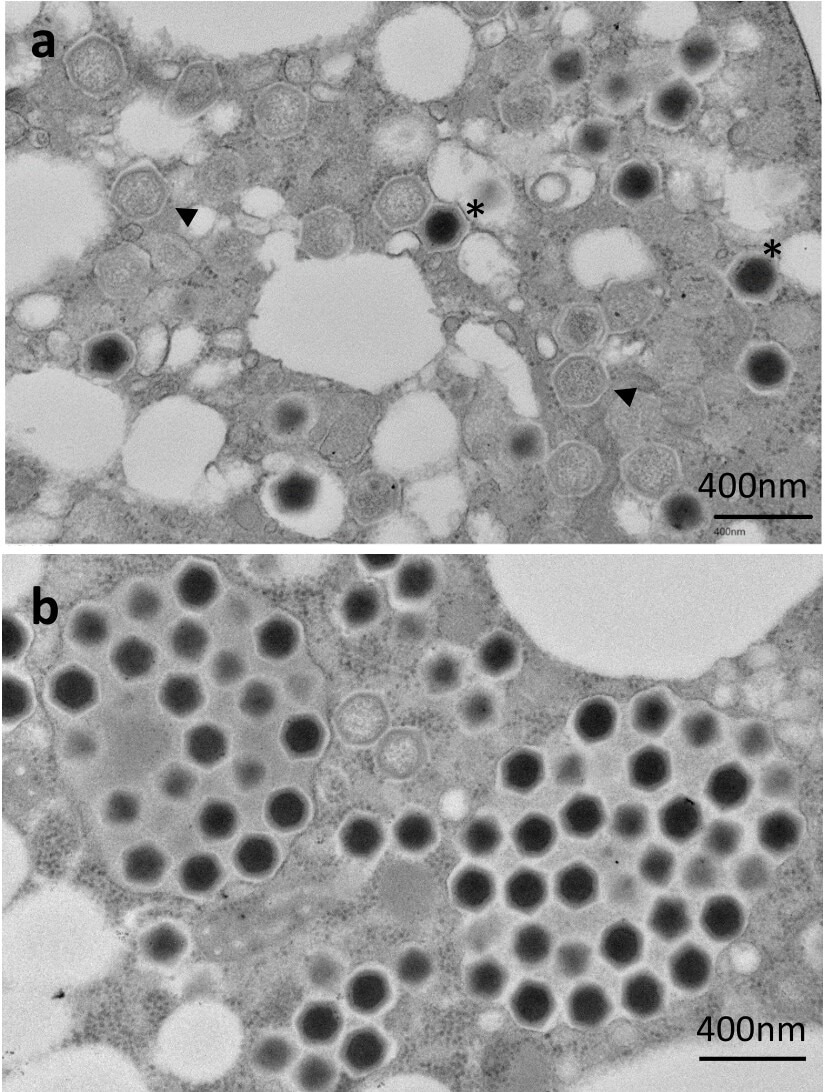

In the present study, researchers comprehensively characterized ushikuvirus by examining its phylogenetic, genomic, structural, and cytopathic properties in Vermamoeba vermiformis. They conducted structural analyses using conventional transmission electron microscopy (c-TEM) and cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM), complemented by single-particle analysis of the viral capsid, achieving a resolution of 9.30 Å.

The researchers performed periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining to investigate surface carbohydrate content and assess capsid glycan components. They cultured vermamoebae long-term in proteose peptone–yeast extract–glucose (PYG) medium at 26 °C to evaluate virus-induced cellular changes. They compared the findings with those of cells harboring Candidatus phylum Dependentiae strain Noda2021, an endosymbiotic bacterium previously isolated from freshwater.

The researchers performed microscopic examination and cell counting to determine cell morphology, size, and number. Tissue culture infectious dose (TCID₅₀) values from the culture supernatants indicated viral infectivity. Researchers examined infection dynamics under several experimental conditions, including infections performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10.

They used electron microscopy to visualize infected Vermamoeba cells at two, four, eight, and 120 hours post-infection; the MOI for this specific EM time-course was not specified. Additionally, they performed time-lapse imaging to monitor cellular movement and the progression of CPE.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS), contig reconstruction, and functional enrichment analysis of predicted open reading frames (ORFs) enabled genomic characterization. The genome was assembled as two contigs, and the team inferred phylogenetic relationships through comparative analyses of conserved viral genes, including major capsid proteins, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) capping enzymes, and family B DNA polymerase.

(a) Genome-containing (asterisks) and empty particles (arrowheads) were detected in the cytoplasm. (b) Numerous full particles were observed in the cytoplasm with or without surrounding membranes.

Structural and Cytopathic Features Distinguish Ushikuvirus From Relatives

The team found that ushikuvirus possesses a large genome of at least 666,605 base pairs, encoding 784 predicted genes and two transfer RNA genes, making it comparable in size to clandestinovirus (582 kbp) but substantially larger than members of the Mamonoviridae family.

Genome annotation revealed a high proportion of ORFans (58 %), with 25 % of ORFs showing similarity to other Nucleocytoviricota viruses, predominantly clandestinovirus sequences. Phylogenetic analyses confirmed a close evolutionary relationship between ushikuvirus and clandestinovirus, while also highlighting clear biological distinctions.

Structurally, ushikuvirus displays an icosahedral capsid with a distinctive surface architecture. Numerous spike-like protrusions, including prominent cap-like structures, form a surface pattern not observed in medusaviruses, resulting in an overall capsid diameter of approximately 270 nm (about 250 nm excluding spikes). Some of these structures exhibit fibrous decorations, and the authors hypothesize that these unusual surface features may contribute to the comparatively slow progression of infection.

Functionally, ushikuvirus exhibited a longer infection cycle and delayed CPE relative to related giant viruses. Infected Vermamoeba vermiformis cells underwent pronounced enlargement, nearly doubling in size within 60 hpi, with some cells increasing several-fold in apparent dimensions, before gradually shrinking. The authors note that this apparent enlargement may partly reflect cell flattening rather than true volumetric growth.

This response contrasts with the rapid host cell compaction induced by other amoeba-infecting giant viruses. Following entry via phagocytosis or endocytosis, ushikuvirus formed cytoplasmic viral factories that progressively disrupted and eliminated the host nuclear membrane, a feature not observed in medusavirus or clandestinovirus infections.

Taken together, these observations suggest that ushikuvirus may rely less on sustained nuclear integrity than its closest relatives, indicating a possible shift in replication strategy within this lineage. The distinct cytopathic features of ushikuvirus suggest novel mechanisms of viral pathogenesis that shed light on diverse virus–host interaction strategies.

Despite suppressing host cell proliferation, ushikuvirus maintained stable infectivity, with TCID₅₀ values sustained for up to 96 hpi. Notably, host cell lysis was not detected, and ultrastructural observations suggest that progeny virions are likely released via exocytosis rather than cell rupture. The team identified two GMC-oxidoreductase proteins, H5 167 and H5 445, which are proposed to be key components of capsid fibers involved in host interaction.

Ushikuvirus Highlights New Strategies in Giant Virus Evolution

The study identifies ushikuvirus as a novel giant virus from a freshwater environment in Japan, closely related to clandestinovirus and phylogenetically proximal to the Mamonoviridae family, yet exhibiting distinct pathogenic and structural features.

Its ability to induce pronounced host cell enlargement, alter cell morphology, and disrupt nuclear membranes underscores unique infection strategies not observed in closely related viruses. The host specificity of ushikuvirus for Vermamoeba, rather than Acanthamoeba, further highlights important evolutionary divergence within this group.

Together, these findings position ushikuvirus as a key taxon for investigating giant virus evolution, host–virus interactions, and the mechanisms that shape viral diversity among eukaryote-infecting dsDNA viruses.

Download your PDF copy now!

Reference

Bae, J., Hatori, N., Burton-Smith, R.N., Murata, K., Takemura, M. (2025). A newly isolated giant virus, ushikuvirus, is closely related to clandestinovirus and shows a unique capsid surface structure and host cell interactions. J Virol, 99:e01206-25. DOI: 10.1128/jvi.01206-25. https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jvi.01206-25